“I’m not dealing with violin soloists as much as I’m dealing with tenors”

By Peter Alexander

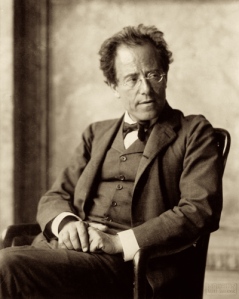

Michael Christie

When I was in Minneapolis March 5–9 for the premiere of Kevin Puts’s opera The Manchurian Candidate at the Minnesota Opera (see review below), I had the opportunity to speak with former Colorado Music Festival Music Director Michael Christie about his life and career since he moved to Minneapolis. Christie, who is now the music director of the Minnesota Opera and conducted the premiere, had interesting observations about the life of symphony conductors vs. opera conductors, how much he loves Minneapolis, and how much he misses his friends from Boulder. Here is a lightly edited version of our conversation:

PA: I understand that you will take your first summer off in how long?

MC: Seventeen years! I’ve been contemplating for a few years what it would look like to actually take a sabbatical. I worked with my manager to identify the summer of ‘15 as an opportunity, and certainly when my wife and I discovered that we were going to have a little boy I thought ‘Oh, this will be fantastic, he’ll be one, my daughter will be seven, it’s a perfect time to just have some time!’ So I’m taking three months off. The coming summers after that will be mayhem. There will be some wonderful announcements about future summers soon, so that’s good.

Is your career mostly opera at this point?

I’d say it’s still 50-50, but doing an opera is a five to seven week time commitment. Doing Carmen or Manchurian Candidate or anything like that takes a big chunk of time, versus doing one orchestral project, which is a week. In terms of the actual amount of time per year it’s heavily weighted toward opera, but in terms of the number of projects themselves, it’s still quite balanced.

Of course, opera preparation time is pretty massive.

Yes, absolutely. Just speaking of Carmen, which we’re doing next month, that score is 750 pages of music! Even though it’s this ubiquitous title, and we generally know the orchestral music (and) a lot of the great arias, there is all of this connecting tissue—hundreds of pages of connecting tissue. And then with the director you have to figure out how is the drama going to work. To do that over 700 pages is a lot of time.

Michael Christie with the cast of “Manchurian Candidate” at Minnesota Opera

And when you do a premiere, nobody has heard a note of Manchurian Candidate until it arrives on your desk.

That’s right, but that’s what’s great about this particular team. (Composer) Kevin Puts and (librettist) Mark Campbell have worked together (before), we’ve worked together as a group, and they are very attuned to what’s happening on stage. So when we make decisions about a tempo or something like that, it will be Kevin who will say, ‘We need to tighten that up,’ or ‘We need more music here.’ He’s not one of these guys who says ‘Two years ago I wrote music and it must remain that way.’ He looks at it and says, ‘Oh, I see, they can’t get the sofa onstage in time, can you repeat those two bars?’ Which is really amazing.

So he’s very practical.

He’s very practical. And there are some times when he just says, ‘Look guys I can’t draw this out any more, you need to tighten up on your side.’ But certainly, it has been very interesting to experiment with the piece, (to) try this a little quicker, or a little slower. It’s been very exciting but wonderfully collaborative.

At this time do you hold any other positions than music director at Minnesota Opera?

All of my work outside of Minnesota Opera is freelance. Music Director at Minnesota Opera is my one title. Having held three at one point, I can tell you one is a good thing.

For many years Christie flew his own airplane to get to and from the three positions he held as music director.

That must give you a lot more flexibility and a lot more control of your schedule.

Yes, that’s exactly right. When I look back at the ebbs and flows of the intensity of life (in) my late 20s and early 30s—Phoenix, Brooklyn, Boulder—sometimes I’m amazed that I survived, because the needs of those organizations beyond doing performances was enormous. It’s good to have been through that, to know now what an organization needs from one of its artistic leaders.

Your wife and your children must appreciate the fact that you now have a more stable lifestyle.

Yes, absolutely, and my wife had been doing all of her medical training during that same time period. We both were on a hamster wheel, just running like crazy. She’s in an amazing medical practice here in Minneapolis, so it’s all just worked out well. So we do have a great life with a lot of interesting opportunities.

And you like Minneapolis?

It’s an amazing place for culture and cuisine. In a lot of the cities I’m visiting around the United States, the food’s just getting much, much better—everywhere, cities large and small. Minneapolis is a city that goes out. People go out of their homes, they go to theater and they go to sports—they just go out, so they want to have a good scene.

Photo by Jared Platt

Do you miss planning an entire symphony or summer season, which gives you the opportunity to a different kind of planning than what you can do with an opera company?

I’m certainly keeping an eye on what’s going on in the business, who’s doing what kind of programming, who’s doing what kind of collaboration, those groups that are bringing more multi-media, interdisciplinary performances. Some of the stuff we had started doing in Boulder, we were thinking in a way that the industry was starting to think as well. I’m very pleased about that. I’m not sure that I miss it per se, but I’m aware that I need to stay on top of it in order to be effective the next time around. It’s a new set of colleagues, and I’m not dealing with violin soloists as much as I’m dealing with tenors.

I won’t ask if that’s an improvement.

Exactly! But it is different. It’s nice when I am doing some of the symphony projects, and if there’s a voice required, I now have a rolodex of people that I can recommend. I don’t view the opera and symphony worlds as segregated. There are more of us that are crossing over and are able to negotiate the needs of both pretty readily, I think.

When you are planning for a symphony, whether it’s the regular season in Phoenix or a summer festival in Boulder, you can do a broader palette of composers and styles, whereas with opera—how many works do you do in a season?

We do five.

Christie in the pit of the Minnesota Opera at the Ordway Music Theater. Photo by Michal Daniel.

And of those you will conduct?

I will do between three and five. It depends on what’s going on outside, but I definitely get your point about variety. You can’t do 24 operas in a season! But at the same time, one thing that I have come to really appreciate is that when you do five operas and you have five weeks for each, you really get to grow into it.

Sometimes in the pressure cooker of a festival or just a normal symphony season, you’re thinking about 10 different programs at a time. If you don’t stay on top of it, you’re not ready to start that next program the minute the previous one ends. There is something quite nice to having a little bit more space to ask yourself, ‘Well, should it and could it be a little bit this, or more of that?’ Whereas sometimes with a symphony you have to show up on that Tuesday morning (to start rehearsals), you have 10 hours and come hell or high water—it’s going to be within a fairly narrow range.

I like that you get to know people a lot better, too. You get to know that group of singers very well, certainly the stage director, but even the orchestra. On one project we’re probably together for 30 hours vs. the 12 for a symphony.

I would guess that the orchestra players would have a different attitude toward the repertoire because while they have played Carmen before, it’s not a Beethoven symphony that they may have played dozens of times before.

That’s right. Some of our orchestra (members) have probably played it twice. I think there isn’t an exhaustion with the repertory. Since the Minnesota Opera does happen to be on quite a great run over the last couple of decades, there’s so much ownership (by the players). And I do think when somebody’s decided to be part of an opera orchestra, there is thinking that goes into how they approach playing together. They know that they play a more supportive role than they would if they were on a concert platform. Opera orchestras know you have to listen, and we have to work this out together.

In opera there are so many different elements to bring together, it seems to me about the most difficult art form. And I don’t know of any job harder than what an opera singer does, mastering the vocal technique, learning all of the music, doing it onstage, in costume, while acting.

I agree. And you have to do it with lights shining on you, and you have this guy down in the pit waving his arms trying to keep together 60 people with you at the same time. Opera is very complicated. When you think about the other art forms that are somewhat similar, Broadway musicals are on a continuum with opera, but that band is 12 people, most of the time keyboards.

And the singers are all miked now.

Right, the singers are all miked. When you think about the cast of Lion King, some of my buddies who do this stuff say they sing with 30% of their voice, 40% of their voice. That’s what you have to do to survive eight performances a week. When you hear an opera singer who’s been going at it all night afterward, and they speak to you, that voice is a little bit strained. It’s such a massive physical undertaking.

Photo by Michal Daniel for the Minnesota Opera.

Is it an increased challenge professionally, moving from orchestral to opera conducting?

I think it just depends on your approach to it. If you want to be a dictatorial conductor who only wants it their way, opera’s not your bag, because you have to be sensitive to what’s going on in the drama. So it’s not that I’ve taken a step up, it’s that I feel like I’ve just opened up my ears, opened up my mind toward different interpretational concepts.

I actually think that when I go back to the symphony repertory now, I can’t help but think—Dvorák for example. Given that he’s written something like nine operas, there’s no way that he wanted people to have relative freedom in his operas, and then absolute rigor: ‘Don’t you diverge one iota from my symphonic writing!’ Sometimes you would think that if you’re doing symphonies, it says an eighth note so it must be an eighth note. Well, maybe that eighth note’s there to facilitate a breath before the next phrase, or whatever that case may be. So I just feel very lucky to have had that training.

I learned when I started listening to opera, that with singers, an eighth note is not just an eighth note.

That’s exactly right. It’s a time for reflection, or it can be a moment of anger, curtness, it can be a moment of pause. That’s what’s fun about those five weeks, that you get to work with the singer on developing, if it’s going to be anger, what do we have to do around that to make that happen, with the lighting, with the orchestra crescendo, etc.

And when you work with a living composer, in an opera like Manchurian Candidate, you realize that at least with certain composers that they’re saying to us, ‘I’m trying my best to write this in a way that gives you as thorough of a road map as possible, but you have to make sure the drama works.’ And that makes me even more convinced that (with) Mozart, Berlioz, these composers that were steeped in both traditions, those traditions definitely overlapped each other. And it gives much more license than we would normally think.

Another thing that I love about opera is that the patrons, the fans—they’re just so rabid. I love that people are as fussy about whether they like the singing of the mezzo singing Carmen as they are about the sets—they’re watching all the elements, they’re listening and wondering, ‘Can I hear this? Can I see that? Why did they make that cut there?’ And they let you know! Which is fine.

I’m sure they do! The outrage over some of the recent Met productions, as intense as it has gotten, is also somehow reassuring, that people care so much about the art form.

I think so, too. I love that. I think it’s healthy and was one of the things that really attracted me to coming to the Twin Cities. First of all, the opera position afforded the opportunity to get involved in that world, but the community itself has very high expectations for everything. So whether it’s education, the environment, or just the community asking ‘Can we access that bike trail? What’s our access to the river like? What’s the quality of life?’ It’s such an interesting thing to be in a community where there’s this underlying expectation of ‘We’re here and it’s got to be good.’ That’s a wonderful bit of pressure for an arts company.

To wrap up: Is there anything coming up that you can share with us? Any future plans, other than having the summer off?

We’ve announced next season. We have The Shining which is our new opera for next year, based on the Steven King novel. It will be by Paul Moravec, the composer, and Mark Campbell is also doing the libretto for that. Unusually, we’re bringing back a production of Magic Flute which was a co-production with the Komische Oper in Berlin. It’s (based on) this fantastic 1920 film. It’s really quite remarkable, it kind of harkens back to my multi-media film with orchestra concepts.

The bigger news starts in 2017. That will start coming in the spring of this year, and we can talk about that when it happens.

Do you have a message for your friends in Boulder?

I miss them all! Every summer was a pivotal time because we tried things and it was fun to see what worked, what had to be changed, and everything that we did together really kind of informs decisions I make, whether it’s opera or symphony. So it’s a special place in my heart.

Note: Edited March 12 for clarity and to correct minor errors of punctuation and typos.

The Ballad of Baby Doe by Douglas Moore

The Ballad of Baby Doe by Douglas Moore