Boulder Opera’s “Operatizers,” Boulder and Longmont symphonies’ Beethoven 3 and 9

By Peter Alexander April 17 at 4:30 p.m.

The Boulder Symphony will present Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3—known as the “Eroica”—along with Grieg’s Piano Concerto and the “Lullaby” for string orchestra by George Gershwin Friday evening (7:30 p.m. April 19; details below).

Devin Patrick Hughes will conduct. Soloist for the Grieg Concerto will be Canadian pianist Lorraine Min, who has toured and performed extensively in North and South America, Europe and Asia.

Originally written as a composition exercise on the piano, Gershwin’s “Lullaby” was arranged by the composer for string quartet. He later incorporated the tune into his 1922 musical, Blue Monday. The show was not a success, and it was not until 1967 that it became better known in performances by the Juilliard String Quartet. Today, performances by full orchestral string sections are common.

Grieg composed his Piano Concerto over the summer of 1868, during a vacation in the village of Søllerød, now part of København, Denmark. Although Grieg was never fully satisfied with the score, the concerto has remained one of his most popular pieces. A review of the premiere praised the concerto as “all Norway in its infinite variety and unity,” and fancifully described the second movement as “a lonely mountain-girt tarn that lies dreaming of infinity.”

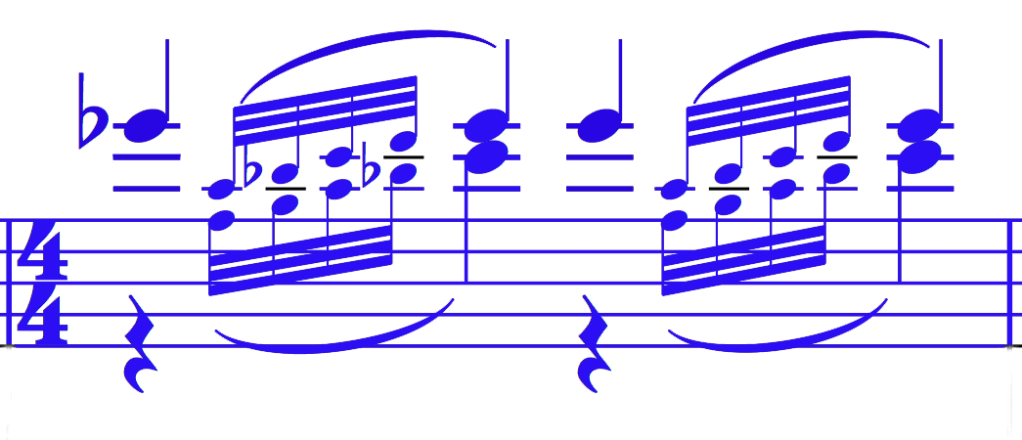

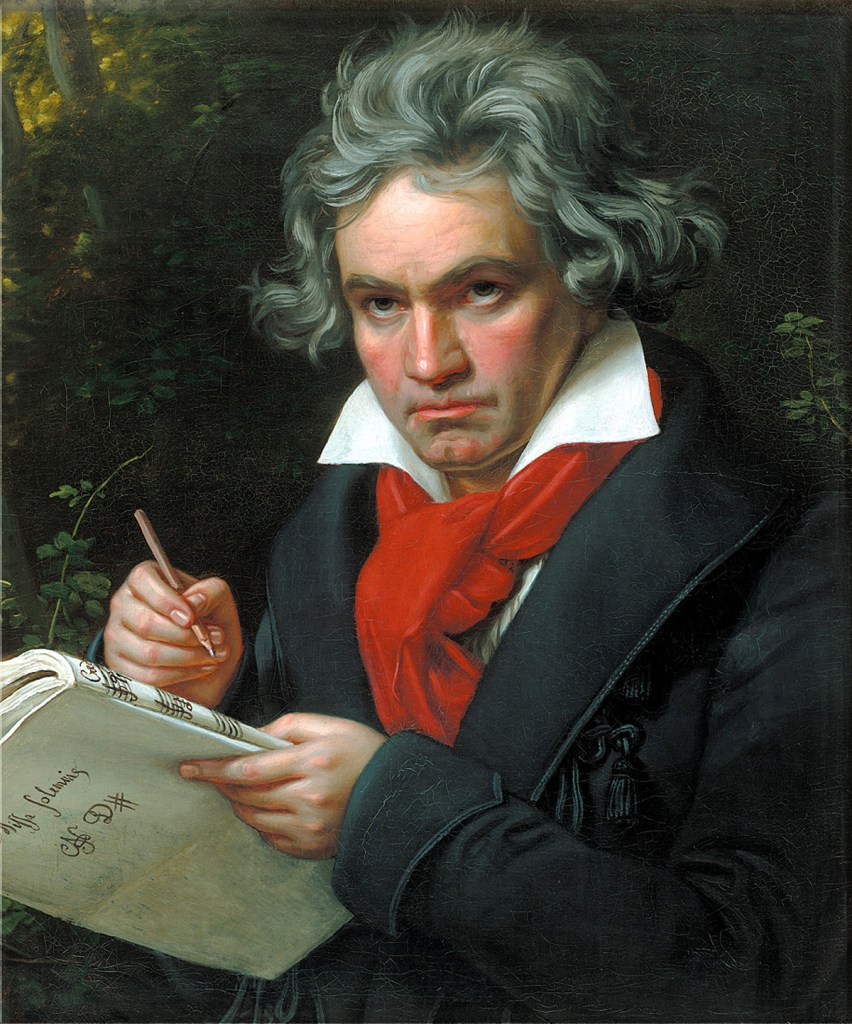

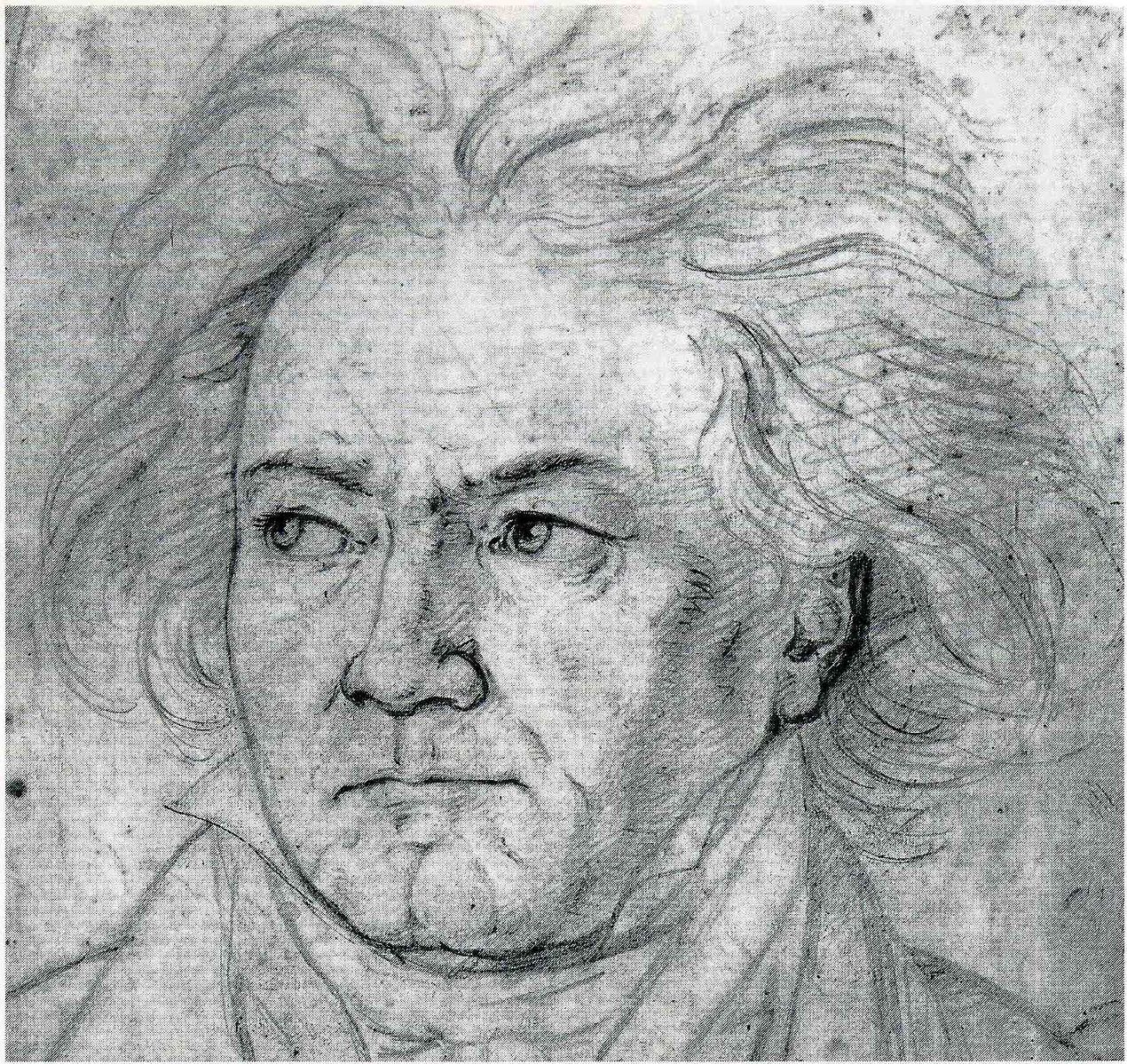

Beethoven’s Third Symphony is one of those musical works that are often described as a turning point in music history. It is nearly twice as long as any previous symphony, and indeed heroic in scope and feeling.

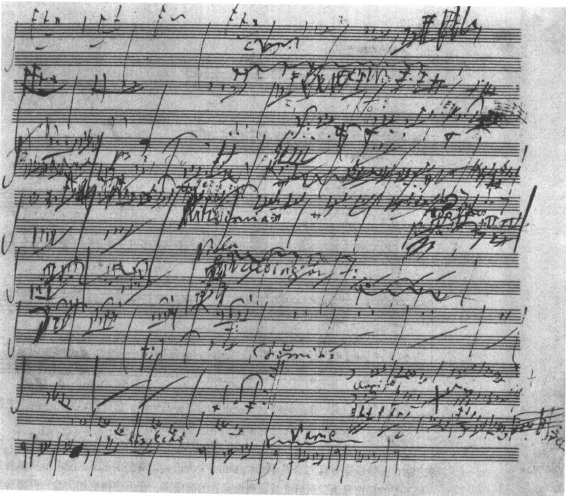

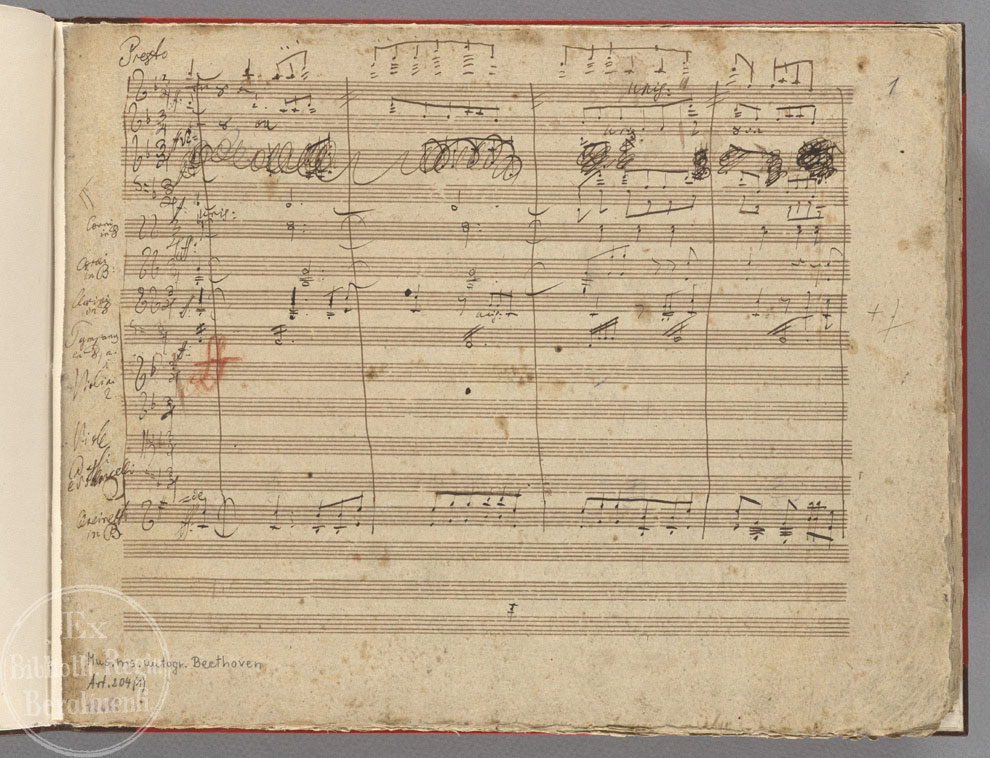

When he wrote it, Beethoven famously titled the symphony “Bonaparte” in honor of Napoleon, but scratched out the dedication in his manuscript when the French general crowned himself emperor. It was published in 1806 with the title “Heroic Symphony . . . composed to celebrate the memory of a great man.”

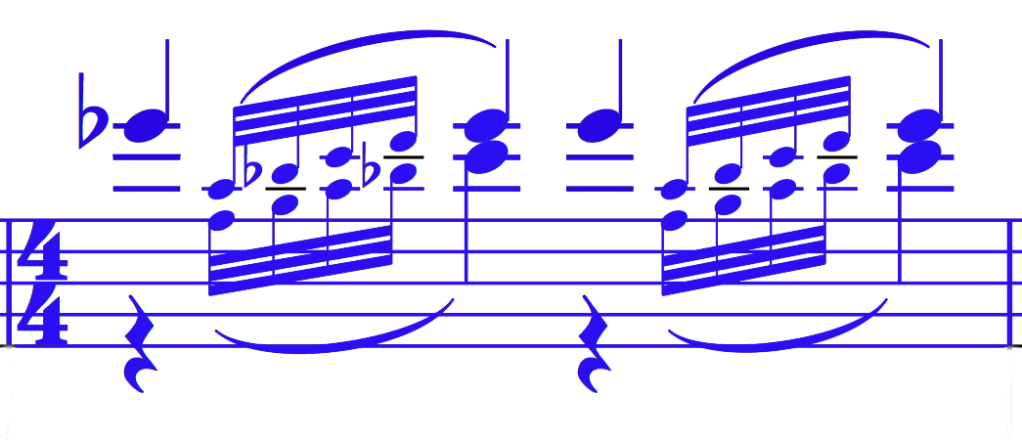

In place of a traditional slow introduction, Beethoven starts the symphony with two brash chords and spins out a lengthy movement starting with only the notes of the tonic E-flat chord. The second movement is an intense funeral march, a much more dramatic and powerful movement than his audience would have expected. In place of the normal minuet, Beethoven composed a rambunctious scherzo.

In these first three movement, the realm of the symphony has been expanded. The finale is more typical of the times, a set of variations on a theme from Beethoven’s ballet The Creatures of Prometheus. But even here, the number of variations, a fugue on the theme and a section of development represent an extension beyond the normal variation finale of the time. Again, Beethoven expanded the scope of the symphony.

# # # # #

Boulder Symphony, Devin Patrick Hughes, conductor

With Lorraine Min, piano

- Gershwin: “Lullaby” for string orchestra

- Grieg: Piano Concerto in A minor

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, op. 55 (“Eroica”)

7:30 p.m. Friday, April 19

Grace Commons Church

# # # # #

Boulder Opera opens the door on “North American storytelling” with “Operatizers,” a program of five short operas by composers from American master Samuel Barber to contemporary operatic star composer Jake Heggie to Ft. Collins-based composer/songwriter Ilan Blanck.

Subjects of the opera include a parody of television soap operas to various meditations on modern love. Performances Saturday and Sunday (7 p.m. April 20 and 3 p.m. April 21 at the Diary Arts Center) will feature a “Maestro’s Reception” at intermission where audience members can meet cast members and directors and ask questions about the productions.

The five operas and their plots are described on the Boulder Opera Web page:

- Avow by Mark Adamo imagines a conflicted bride, her avid mother, the haunted groom, the ghost of his father, and a celebrant who really should make better efforts to remember which ceremony he’s performing.

- At the Statue of Venus by Jake Heggie tells the story of an attractive woman waiting in a museum by the statue of the goddess of love to meet a man she has never seen before. Will he like her? Will she like him? We all know Mr. Right doesn’t exist – or does he?

- A Hand of Bridge by Samuel Barber consists of two unhappily married couples playing a hand of bridge, during which each character has a brief aria expressing his or her inner desires.

- Gallantry by Douglas Moore is parody of hospital soap operas with commercial interruptions.

- Spare Room with a Shag Rug by lan Blanck is written in English and Spanish, plus a touch of Yiddish, paying homage to the composer’s own Mexican-Jewish heritage.

# # # # #

“Operatizers”

Boulder Opera Company

- Mark Adamo: Avow

- Jake Heggie: At the Statue of Venus

- Samuel Barber: A Hand of Bridge

- Douglas Moore: Gallantry

- Ilan Blanck: Spare Room with a Shag Rug

7 p.m. Saturday, April 20

3 p.m. Sunday, April 21

Dairy Arts Center

TICKETS, including add-on tickets for the Maestro’s Reception at intermission

# # # # #

The Longmont Symphony Orchestra (LSO) and conductor Elliot Moore conclude their cycle of all nine Beethoven symphonies Saturday (7 p.m. Vance Brand Civic Auditorium; details below) with the massive Ninth Symphony, one of the symphonic icons of the 19th century.

The Longmont Chorale joins the LSO for this performance. Soloists will be soprano Dawna Rae Warren, mezzo-soprano Gloria Palermo, tenor Javier Abreu and bass-baritone Michael Leyte-Vidal. The LSO has performed the full Beethoven cycle over the past five seasons, starting in April, 2018.

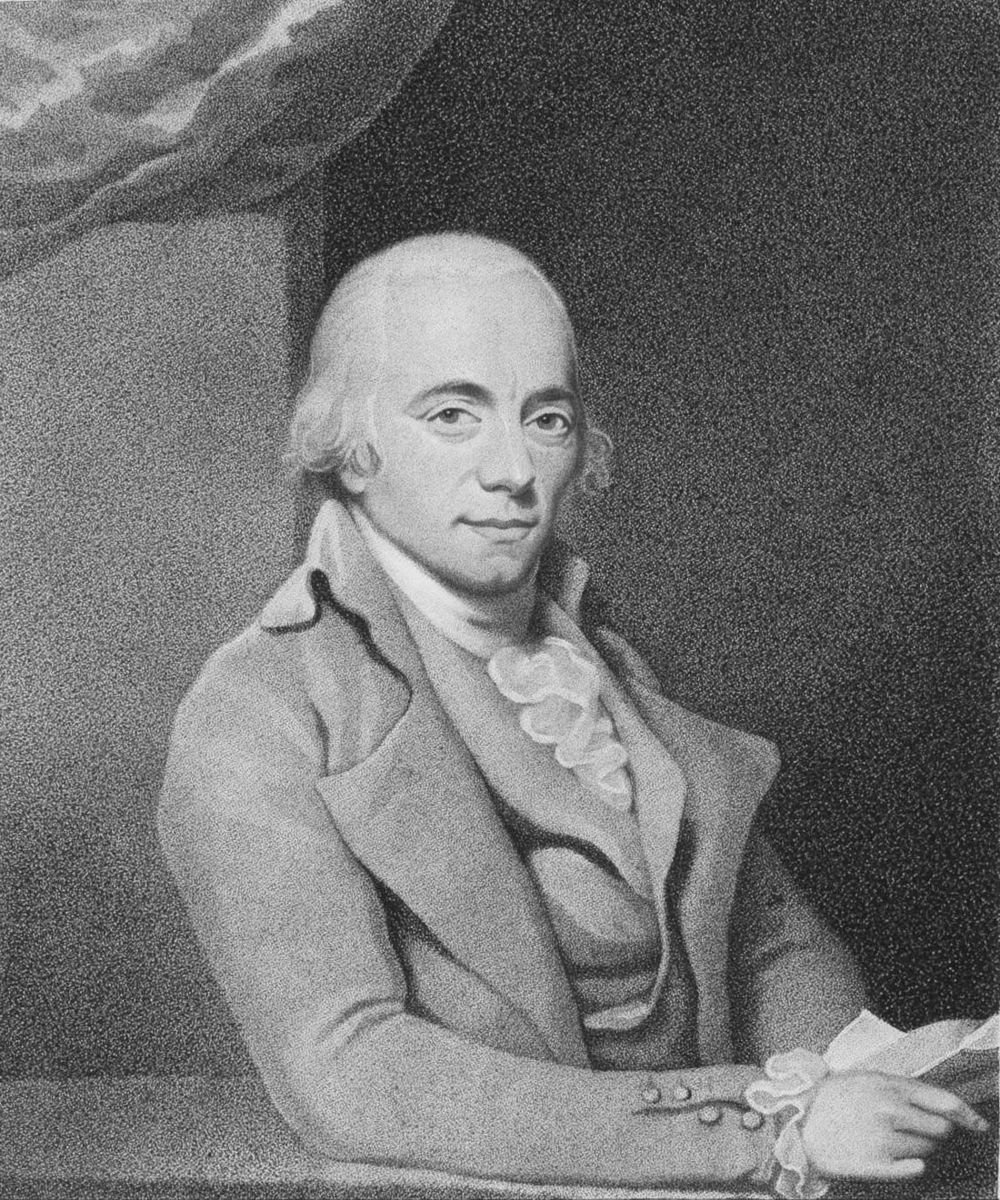

Vaughan Williams wrote his Serenade to Music, based on a text by Shakespeare, as a tribute to conductor Henry Wood. Scored for orchestra and 16 vocal soloists, it was later arranged for orchestra with four soloists and chorus. Since the first performance in 1938, it has been loved by singers and audiences both for the sheer beauty of the vocal writing and the harmonies.

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the first by a major composer with chorus in addition to orchestra, is one of the most performed and most loved works in the classical repertoire. It was composed in 1822-24, and first performed in Vienna May 7, 1824.

The orchestra was led by Austrian composer and violinist Michael Umlauf with Beethoven, stone deaf by that time, standing at his side. In one famous anecdote, the composer was unable to hear the cheers of the audience at the end of the performance and the alto soloist, Caroline Ungar, had to take him by the hand and turn him around to see the enthusiasm of the listeners.

The choral last movement uses a text by German poet Friedrich Schiller that celebrates the brotherhood of men: “All men shall become brothers, wherever the gentle wings [of joy] hover. . . . Every creature drinks in joy at nature’s breast.” Because of this message of universal love, the symphony has been performed for many special occasions in history, including the original opening Wagner’s Bayreuth Festspielhaus (festival hall) and for its reopening after World War II, in 1989 to celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall, and for the opening of the 1988 Winter Olympics in Japan, and other ceremonial occasions.

Performances of the Ninth Symphony are almost always considered special occasions, and almost always sell out. In addition to its popularity, the symphony has influenced composers from Dvořák to Bartók, and especially the symphonies by the Austrian composer Anton Bruckner.

# # # # #

Beethoven Cycle: Symphony No. 9

Longmont Symphony, Elliot Moore, conductor

With the Longmont Chorale, Nathan Wubbena, conductor

Soprano Dawna Rae Warren, mezzo-soprano Gloria Palermo, tenor Javier Abreu and bass-baritone Michael Leyte-Vidal

- Vaughan Williams: Serenade to Music

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor (“Choral”)

7 p.m. Saturday, April 20

Vance Brand Civic Auditorium

TICKETS (Note: This concert is close to selling out. Availability of tickets cannot be guaranteed.)