Violinist Ed Dusinberre and violist Richard O’Neill will play Mozart

By Peter Alexander Feb. 27 at 5:15 p.m.

The Boulder Chamber Orchestra (BCO) traces the history of classical music on their next concert (7:30 p.m. Saturday, March 1; details below), with a concerto grosso from the Baroque era, music from the heart of the classical style, and a symphony pointing the way to the early Romantic era.

The concert under conductor Bahman Saless will feature violinist Edward Dusinberre and violist Richard O’Neill from the Takács Quartet playing Mozart’s exquisite Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola with orchestra. Two of the superstars of the classical music world, Dusinberre and O’Neill are hailed in the concert’s title as “Boulder Celebrities.”

Works framing the Mozart are the Concerto Grosso in F major attributed to Handel, and Schubert’s Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major. All three are bright and cheerful works, giving the entire concert an uplifting spirit.

With its two soloists, the Mozart stands as the centerpiece of the program. Dusinberre and O’Neill know each other well, having played together in the Takács since the latter joined the group five years ago. In addition to their work in the quartet, they both have concert and recording careers as soloists and both have won a classical music Grammy.

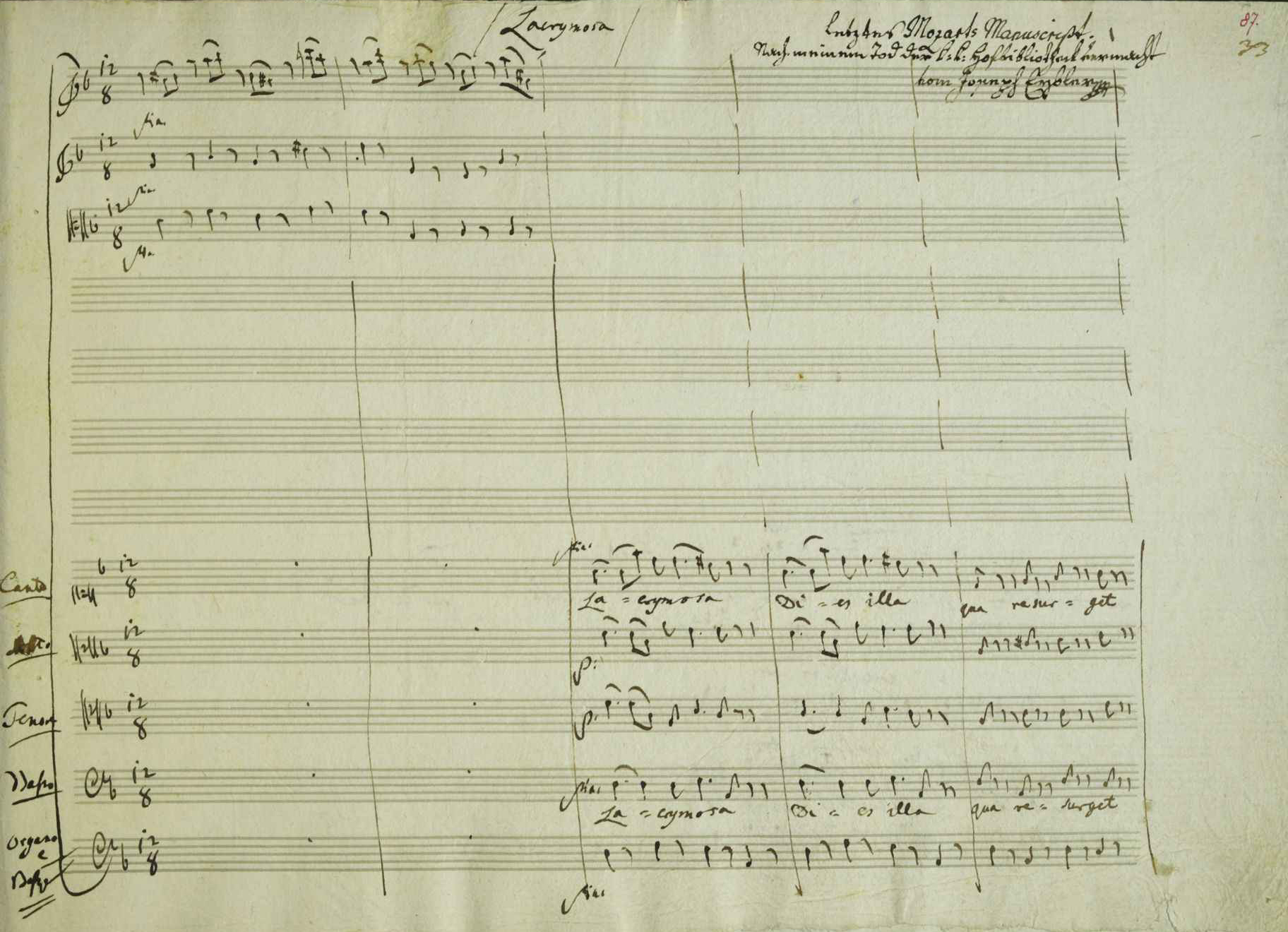

Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante is one of the composer’s most loved pieces, and one that O’Neill has played many times. “For some violists it’s the reason they play the viola,” he says. “It’s such an amazing work, and it has been a lifetime dream for me, visiting it through different stages of my life. (There is) the joy of playing it over the years with different orchestras and different violinists, each having their own distinct views on the piece.”

He says he learns from every violinist he plays it with, but this is his first time with Dusinberre. And it’s a special experience playing with someone he knows so well from their work together in the Takács.

“Part of the magic of being in a string quartet is that you spend so much time with your colleagues, and you get to know them under many different circumstances,” O’Neill says. “I’ve played (the Mozart) with brilliant soloists, but this time with Ed we’ve been able to dig into the more psychological aspects of the music, because we already know each other’s playing pretty well.”

In other words, O’Neill and Dusinberre were able to skip past the early stages of getting to know a musical partner and get down to details right away. The quartet just returned to Boulder from a tour, but they were able to rehearse Mozart together on the road, O’Neill says. Now, “I’m really looking forward to working with the orchestra and Bahman (Saless),” he says.

One thing he urges the audience to tune into with the Sinfonia Concertante is how the two solo parts relate to one another. “Mozart pairs the violin and viola like they’re operatic characters,” he explains. “It’s like a conversation.

“The person that talks first often frames the way the conversation will go. In the first movement, the violin says, then the viola says, and then the violin says and the viola says. There’s a lot of playful discussion, and then in the recapitulation—the viola says it first!”

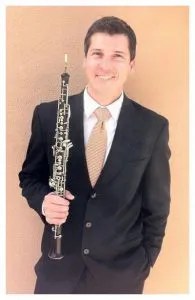

The concerto grosso was a form common in the Baroque period, featuring a small group of soloists with orchestra. The Concerto Grosso in F features two oboes with a string orchestra. The soloists will be guest artist Ian Wisekal and BCO member Sophie Maeda.

The Concerto is “attributed to Handel” because publishers of the time often printed and sold works that had been pirated, or changed the name of the composer, making authenticity uncertain. In the case of this concerto—which is certainly an authentic representative of the Baroque style—it has appeared under Handel’s name and as an anonymous composition.

Schubert wrote his Fifth Symphony in 1816, when he was 19 years old. It is the most classical of Schubert’s symphonies, having been written for a smaller orchestra, with one flute and no clarinets, trumpets or timpani. Schubert was infatuated with Mozart’s music, and wrote in his diary ”O Mozart, immortal Mozart!”

At the time he was unemployed, hanging out with a group of young artists, poets and musicians. The first reading of the symphony was given by this circle of friends in a private apartment, with the first public performance occurring 13 years after Schubert’s death.

The music of the symphony is often described as “Mozartian” in its gracefulness and melodiousness. It conforms closely to the standard four-movement structure of the classical period, with a minuet movement in third place. At the same time, the harmonic palette suggests the Romantic style to come, particularly in Schubert’s works of the remaining 12 years of his life.

But regarding the program’s title, the question of classical musicians being genuine “celebrities” might be debatable—but if it’s possible it would be in Boulder, where the Takács Quartet routinely sells out two performances of every program.

Superstars or celebrities, Grammy winners both, Dusinberre and O’Neill are always worth hearing.

# # # # #

“Boulder Celebrities”

Boulder Chamber Orchestra, Bahman Saless, conductor

With Edward Dusinberre, violin, and Richard O’Neill, viola

- Handel: Concerto Grosso in F major, op. 3 no. 4

- Mozart: Sinfonia Concertante in E-flat major for violin and viola with orchestra, K364

- Schubert: Symphony No. 5 in B-flat major, D485

7:30 p.m. Saturday, March 1

Boulder Adventist Church, 345 Mapleton Ave.