“Voice of Nature” will feature songs and a film from National Geographic

By Peter Alexander Jan. 22 at 5:50 p.m.

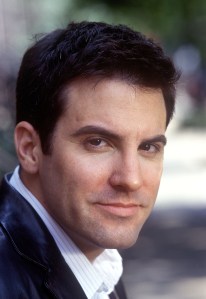

Soprano Renée Fleming will come to Macky Auditorium next week (7:30 p.m. Friday, Jan. 31) to present a program that she developed while cut off from her professional life during the COVID pandemic of 2020–21.

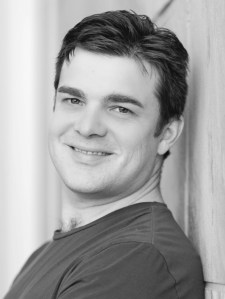

Titled “Voice of Nature: The Anthropocene,” the concert features Fleming and pianist Howard Watkins. The repertoire draws on a Grammy-winning album of the same title that Fleming recorded in 2023 with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, music director of the Metropolitan Opera, as pianist, and features songs that mention or reflect on the natural world. Part of the program will be accompanied by a film produced by the National Geographic Society.

“During the pandemic, the most comforting and healing activity for me was just being outside,” Fleming says. “Walking every day, gardening—to the point that I didn’t even want to come in. I always found it interesting that art song, especially the 19th century, also the 18th century and early 20th century, uses poetry that brought nature into the conversation about any aspect of the human condition. I found that interesting, in comparison with new works, which very often never mention nature.”

In that context, she worked with Nézet-Séguin to put together an album of songs that celebrate the consoling and healing power of nature. She decided to commission new songs from three living composers—Kevin Puts, Nico Muhly and Caroline Shaw—to bring the program up to today, and combine them with selected pieces from the extant song literature.

“It was really fun to put the program together,” Fleming says. For the 19th-century art songs, “obviously I had to find things I thought would suit Yannick (Nézet-Séguin), give him enough of an interesting program that he would want to play it. And also because Yannick is French-Canadian, (the French) language works beautifully for him.”

The result is an album that features some very lovely but unfamiliar songs by Gabriel Fauré and Reynaldo Hahn, both French composers of the early 20th century, and also songs by Liszt and the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg. “I just chose beautiful music that has powerful poetry and stuff I hadn’t performed before,” Fleming says. “I had performed Grieg, I had not performed Hahn at all, and I was thrilled to put Fauré” on the program.

The next step occurred when the album won a Grammy. Fleming decided to take a version of the program on tour, but with some additions. “Rather than just doing ‘Voice of Nature,’ the album, I added some more popular things that I’ve recorded and never perform, like a Björk song and a selection from Lord of the Rings,” Fleming explains. She also added songs by Burt Bacharach and Jerome Kern, and one of the most popular operatic arias in her repertoire, “O mio babbino caro” from Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi.

The final musical addition is a recording Fleming made of Jackson Browne’s “Before the Deluge” together with the Grammy winning folk singer/fiddler and opera composer Rhiannon GIddens, multi-Grammy winning bluegrass singer/fiddler Alison Krauss, and Nézet-Séguin, in an arrangement by composer Caroline Shaw. The recording will be played about halfway through the concert intermission.

Once she committed to the tour, Fleming had another idea: “I thought, let’s take this on the road but I’d like to have film with it,” she says. “I said, I’d really like to do something that shows the planet and encourages us to protect it.

“I happened to meet someone who worked with National Geographic at a dinner party. I was telling him about it and he said ‘I can introduce you to the head of National Geographic.’ So I had a two minute Zoom call with the CEO (Michael Ulica), and he said, ‘We’re looking for influencers and we’ll make your film.’ They did it in about three weeks and I’ve been touring it ever since, because it’s a beautiful piece.”

Fleming says that her devotion to nature and the planet dates back a long way. “When I was a teenager I saw a film that had a huge impact on me,” she says. “The film came out in the ‘70s, Soylent Green.

“The scene that really had a powerful effect on me was the one in which Edward G. Robinson, who was dying of cancer, (played a scientist who) had signed up for end of life care, and was looking at beautiful pictures of earth, and none of that existed anymore. I thought, ‘How could that possibly ever happen?’ And here we are, later in my life—if we don’t get a handle on this, I think we’re ultimately talking about the destruction of us on the planet.”

In an artist’s statement on the “Voice of Nature” program, Fleming writes: “Thankfully, the stunning natural world depicted in (the National Geographic) film still exists, unlike that movie scene so upsetting to my younger self. In blending these beautiful images with music, my hope is, in some small way, to rekindle your appreciation of nature, and encourage any efforts you can make to protect the planet we share.”

# # # # #

“Voice of Nature: The Anthropocene”

Renée Fleming, soprano, and Howard Watkins, piano

- Hazel Dickens: “Pretty bird”

- Handel: “Care Selve” from Atalanta

- Nico Muhly: “Endless Space”

- Joseph Canteloube: “Bailero” from Songs of the Auvergne

- Maria Schneider: “Our Finch Feeder” from Winter Morning Walks

- Björk: “All is Full of Love”

- Heitor Villa-Lobos: “Epílogo” from Floresta do Amazonas (piano solo)

- Howard Shore: “Twilight and Shadow” from Lord of the Rings

- Kevin Puts: “Evening”

- Curtis Green: “Red Mountains Sometimes Cry”

- Burt Bacharach: “What the World Needs Now”

—To be played halfway through the intermission—: - Recording of Jackson Browne: “Before the Deluge” (arr. by Caroline Shaw) by Rhiannon Giddens, Alison Krauss, Renée Fleming; with Yannick Nézet-Séguin, piano

- Gabriel Fauré: “Au Bord De L’eau”

—“Les Berceaux” - Edvard Grieg: “Lauf Der Welt”

—“Zur Rosenzeit” - Puccini: “O mio babbino caro” from Gianni Schicchi

- Jerome Kern: “All the Things You Are”

- Andrew Lippa: “The Diva”

7:30 p.m. Friday, Jan. 31

Macky Auditorium

NOTE: Very few tickets are left for this performance. You can check availability HERE.