What can we learn from the collapse of the Colorado Masterworks Chorus?

By Peter Alexander

The collapse of the Colorado Masterworks Chorus (CMC) last month, and the story of the unpaid musicians the organization left behind, were reported in several media at the time (see the Boulder Daily Camera and Denver CBS 4).

The CMC was formed in 2016 and gave its first performance during the summer, presenting the Brahms Requiem under conductor Evanne Browne. In October 2016, the CMC appeared with the Pro Musica Colorado Chamber Orchestra and conductor Cynthia Katsarelis in two performances of Haydn’s Creation.

Their next performances were March 3, 2017, in Denver and March 4 in Boulder, when they presented Handel’s large-scale oratorio Israel in Egypt. For those performances, the CMC engaged a chorus, some of whose members had written contracts and were paid for their performances, as well as soloists and an orchestra. The performances were led by conductor Vicki Burrichter, who also had a written contract as artistic director and was paid.

However, the orchestral musicians, including Katsarelis as concertmaster, and others who were involved in the preparation and performance of the oratorio did not have written contracts, and were not paid.

Michael Madsen, the organizer and board chairman of the CMC had expected ticket sales and a silent auction to cover most of the costs of the performance, but they fell far short of expectations. With somewhere between $12,000 and $16,500 in unpaid bills, Madsen filed dissolution papers with the Colorado Secretary of State’s office to abolish the organization, and ambitious plans for several future performances were cancelled.

That was the situation at the end of March, when the news stories appeared about CMC’s collapse. Today little has changed, and many of the musicians remain unpaid. Musician Relief, a campaign through Colorado Gives that aims to solicit private gifts to pay the musicians, has so far raised about half of its $16,500 goal.

From the money that has been raised, some of the musicians who performed with the CMC have received funds to make up for their loss. As freelance musicians, many of them depend on income from performances to pay their basic expenses, and some of the players had incurred expenses for travel and/or babysitting.

People involved in the performances have expressed differing opinions on how the CMC handled its business and why it broke down. I do not wish to throw fuel on dying embers by going over those disagreements. Nor do I wish to give a forum for accusations against any individuals. More important is a larger question: What does this mean for musicians and musical organizations in the Boulder area? What can we learn from what happened?

From talking with people directly involved in the CMC and its collapse, I found five major lessons for other arts organizations, for their board members, and above all for musicians.

It is very difficult, and takes time, to establish a new arts organization. Anyone who wants to do so needs to have a solid financial plan extending for two or more years, until the organization can qualify for grants. Most arts organizations make no more than 1/3 of their costs from tickets and other sales, with the other two thirds coming from supporters’ contributions and grants. Without one of those three legs, organizers need to be prepared for initial deficits.

Michael Allen, president of Local 2623, Denver Musicians’ Association

Few new arts organizations survive. Michael Allen, the president of Local 2623 of the Denver Musicians Association, has seen this firsthand. “Any time I see a new group, I’m thinking, ‘Why?’” he says. “It really doesn’t make any sense, unless there is a unique point of view. There are a couple of groups that have cropped up in the last decade that have that unique point of view, but they’re in the minority.”

Among the issues making survival difficult is the fact that Boulder is already saturated with musical organizations. There is a great deal of competition for dates, and many weekends see multiple events competing for the same audience. For just one example, early in April there were events in Boulder and Longmont by Pro Musica Colorado Chamber Orchestra, the Boulder Chamber Orchestra chamber series, the Boulder Symphony, the Boulder Opera and the Longmont Symphony, all on the same Saturday evening.

Madsen seems to have underestimated the competition for the group. He complains about the Boulder Film Festival that was the same night as the Handel performance in Boulder, although those may not have been the same people that would have attended a Handel oratorio. But even more challenging than direct conflicts with performance dates is the competition for audience interest and financial support. There are many organizations to support in Boulder, and established patterns of support are very hard to change.

Madsen expected that the quality of the group would be enough to capture support. “I thought we could get by [the competition] by getting the best singers in the front range,” he says. “The chorus was superb, but I was wrong about that, because very good, extremely prepared doesn’t bring the (audience) in here.”

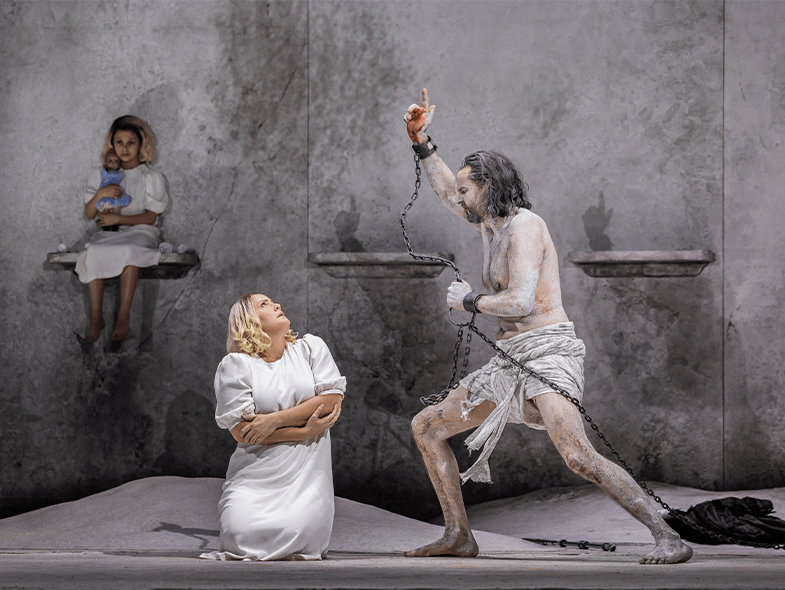

Vicki Burrichter conducted performances of handle’s Israel in Egypt in March

Most people seem to agree with Madsen that the chorus was superb. “It was an excellent chorus, “ Burrichter says. “When you get professional level voices, it automatically raises the level of the chorus. We had a great time and the Handel was spectacular.”

That level of quality may attract attention, but one spectacular performance is not enough to change people’s patterns of support overnight, which is what Madsen was counting on. When that failed to materialize, the organization was left with bills it could not pay. Or as Burrichter says, “It was very, very beautiful and moving, but unfortunately it was on the backs of the instrumental musicians.”

Consult with people who know the business. Several of Madsen’s expectations were unrealistic, as he himself now admits. “Always before when we had done this, we were doing it for larger organizations,” he says. That experience led him to overestimate how much money the CMC would bring in during its first years. For example, Madsen hoped the silent auction would bring in a significant amount of money toward the cost of the performances.

“We were hoping for a $15,000 auction,” he says. That estimate was based on his experience with a refugee ministry, but that is very different than raising money for an arts organization. For her part, Burrichter recognized the problem. “As somebody who’s been artistic director with boards that have done silent auctions, I could tell pretty early on that the silent auction was not going to be successful,” she says. “There were just a lot of errors.”

The $10,000 that Madsen budgeted for ticket sales was also unrealistic. By reports, the Handel performance in Denver had an especially small audience. “I could have told him, having been a musician in Denver for 10 years, that you’re not going to build an audience in Denver overnight,” Burrichter says.

Once again, more caution and better advice would have prevented unrealistic budgeting. “No musical event is paid for by ticket sales and one very humble fundraising attempt,” Katsarelis says. “A little bit of research and planning would have exposed the flawed nature of the plan. They just didn’t know what to expect because they hadn’t asked people who know.”

Everyone involved must understand and follow non-profit laws and best practices. This may be the most contentious area of disagreement among the people involved in the CMC: whether it was run with appropriate board oversight, or Madsen made decisions on his own. For his part, he says only “my wife and I were simply on the board.”

Kathy Kucsan spoke with people affected by the CMC’s collapse

Kathy Kucsan, a consultant who works with arts organizations in Colorado, has spoken with some of the people affected by the CMC’s dissolution. “It sounds like the board of directors wasn’t really a functioning board,” she says. “The board has legal and fiduciary responsibility for the organization.

“From my point of view I would say set up your organization properly” is the most important lesson to be learned.

An attorney would have to clarify the legality of actions that were taken, and no one has claimed that laws were broken. However, several issues have cropped up in background conversations about the CMC that, if true, would be violations of good nonprofit governance. Three are particularly troubling.

The first is that board members were not given enough information on the finances and business practices of the organization. Burrichter says that Madsen “didn’t tell the board what was going on in terms of finances beyond certain very basic things. I’m sure the board didn’t know that (the instrumental musicians) didn’t have contracts.” That information is well within the board’s area of responsibility and if they were not kept informed, they should have been.

Second, Burrichter says that she was excluded from most board meetings, where she could have offered advice that would have prevented some of the miscalculations leading to the CMC’s failure. “I requested to go to a board meeting at one point, but (Madsen) said no, I just want to you to come once a year to talk about the artistic vision.”

It is extremely unusual that an artistic director, who is asked to carry out the objectives of the organization, would not be present and offer advice at meetings where the decisions are made. In hindsight, Burrichter says, “I should have insisted that if I were not going to be on the board, I would not take the job.”

The final question that has been raised is whether the dissolution of the CMC was done properly. This requires action by the board and should not be done by any one individual. Madsen says that he carefully followed a “20-point checklist” from the Secretary of State’s office for dissolving the organization, but has offered no more details.

None of the board members was willing to speak on the record, but I have heard from numerous people close to the organization and the board that, as one person who asked not to be named wrote to me, “The board was just as shocked as everyone else that the Madsens dissolved the chorus.”

These questions show how important it is for anyone who is thinking of starting a nonprofit group, or for anyone who is asked to serve on a nonprofit board, to do their homework. “There are so many resources for brand new nonprofits,” Kucsan points out.

For example, the Colorado Nonprofit Statutes are easily available online. There are simplified guides to the statutes here and here, and the Colorado Nonprofit Association has posted Principles and Practices for Nonprofit Excellence. Other resources are easy to find through online searches.

Too often, supporters are asked to serve on a board without adequate understanding of the responsibilities of board members. In the case of the CMC, it is possible that better preparation and understanding by all the board members, including Madsen, would have prevented some of the problems that occurred.

Freelance musicians need to protect themselves from being exploited. This may mean that they may no longer be willing to play without a written contract. One way to accomplish this of course is to go through the musicians’ union for all engagements.

That is clearly the preference of Allen and the union local in Denver. “We sent a fairly strong message to the union musicians that participated in that production that if they want their union to step in for them, they need to do things under union rules,” he says. “That includes both playing for scale and only working under a contract.

“If a contract had been filed, the union would have paid the musicians and then we would have used our resources to go after the Colorado Masterworks Chorus to seek reimbursement. That was sort of an expensive lesson for (the musicians) to learn.”

In the past, union musicians who took jobs below union scale would have been punished by the local, but Allen says that is not the approach today. “What we try to do is treat this as a teachable moment,” he says. “This is an opportunity to inform a larger group of people about not only what the union could have done, but also why we have the rules that we have.”

With or without the union, it is likely that musicians in Boulder will be more reluctant to take jobs without written contracts. “This is where I think things in Boulder are going to change,” Katsarelis says.

“We’ve always gone on trust, and it’s been reasonable to do that. But (after this) I think that organizations and musicians are going to tighten up and require contracts, instead of the trust method. I don’t think I’m going to play a gig like this again, that isn’t contracted through the union.

“That means they’ll have to pay union scale, which is higher than the kind of prevailing rate, and this is going to stretch the budgets of organizations that hire professional musicians.”

Cynthia Katsarelis, artistic director Pro Musica Colorado and concertmaster of the Handel performances.

Katsarelis says that one final lesson is for everyone who is interested in, attends, or supports musical performances to understanding the real cost of musical performances. “Professional music making in our region is underfunded,” she says. “I wish we could make a stronger case for what high quality professional music making brings to a community.

“This awful debacle that robbed some of the region’s most compelling musicians asks the community to respond in several ways. We have a fundraiser to right that injustice, but there also has to be a response to what high quality professional music making really costs and the value it brings.”

At the end of the day, Kucsan says, “It’s just unfortunate, and it’s a learning experience for everybody involved. You actually have to try, and ask, and sweat the first couple of years, and if you’re still here, there’s a place for you. But to pack it up and leave people in the lurch is not the way to do it.”

You may make a contribution to help the musicians who were not paid by Colorado Masterworks Chorus at the Colorado Gives Musician Relief page, sponsored by the Pro Musica Colorado Chamber Orchestra.

NOTE: Edited for clarity and correction of typos 4/26.

NOTE: Upon reflection, I have now blocked further comments on this article and removed all comments naming or blaming others in the dispute between the musicians and the organizers of the Colorado Masterworks Chorus. No purpose is being served by finger pointing on this site.

I believe there are two important issues for readers, and I will remain focused on those:

- Lessons can be learned from this fiasco. That was the focus of my article, and I believe it remains the main subject of interest for anyone who was not directly involved.

- Musicians who gave their time and talent, and whose livelihoods depend on their professional activities, remain unpaid. I urge anyone who is concerned with the health of Boulder’s musical scene to make a contribution through the page listed above.