Poul Ruder’s Thirteenth Child is “an opera of expressive breadth and depth”

By Peter Alexander Aug. 4 at 11:45 p.m.

Santa Fe Opera has five operas in production this summer, continuing through Aug. 24. Reviews of three of those productions—Puccini’s La bohème, Bizet’s Pearl Fishers and the world premiere of The Thirteenth Child by Poul Ruders—are below. Reviews of the remaining two productions will appear in a later blog post.

Soloman Howard (Colline), Zachary Nelson (Marcello), Dale Travis (Benoit), Will Liverman (Schaunard), supernumerary, and Mario Chang (Rodolfo) in La Bohème. Photo by Ken Howard for the Santa Fe Opera.

La bohème, the most familiar of the operas on Santa Fe’s 2019 schedule, is certainly enjoyable. The firmly realistic set and production are mostly serviceable, if not spectacular, and the singers range from reliable to impressive. Conductor Jader Bignamini knows when to stretch the tempo and when to push ahead. If he sometimes took the faster bits a little too fast, the excellent orchestra stayed with him, responding well to every push and pull. Their performance was thoroughly idiomatic, always giving the lyric moments time to blossom.

My one criticism of Bignamini’s work is that he was not careful enough to maintain a good balance between stage and pit. He has conducted in Santa Fe before—Rigoletto in 2015—so he should know the theater’s acoustics, but he sometimes allowed the voices to be swallowed by the orchestra.

Eliot Page as Parpignol with the Santa Fe Opera Chorus and Children’s Chorus. Photo by Ken Howard.

Scenic designer Grace Laubacher had mixed success adapting to the Santa Fe stage. Her garret, a stand-alone piece that was pushed on for the first act and that visibly cracked apart at Mimi’s death in the third act (symbolizing the emotional shattering of the remaining characters?), was effectively evocative of 19th-century Paris. The second act, using movable pieces that were miniature buildings from one side and flat semi-reflective surfaces on the other, were an uncomfortable solution for the streets outside the Café Momus, with the toymaker Parpignol popping above a multi-story building like Godzilla in Tokyo.

Mario Chang (Rudolfo), Gabriella Reyes (Musetta), Vanesssa Vasques (Mimi) and Zachary Nelson (Marceloo) in Act III of La Bohème. Photo by Ken Howard.

Most successful was the third act. The minimal set pieces—the outside of the cafe, the city gate and a snow-covered tree—were all that was needed. The spare set contributed to the bleakness of the winter scene.

Mary Birnbaum’s direction was ideal for the highjnks of the four artists sharing the garret, capturing their camaraderie well. At other times, however, her ideas got in the way of the story. Having the characters pass downstage of the garret to reach its door proved distracting. Characters did not always seem to interact.

The visual pun of having Musetta enter on inline skates, suggesting how she glides through life and the streets of Paris, might work if the Musetta were comfortable on the skates, but soprano Gabriella Reyes seemed not to be as she careened from light post to light post, sometimes supported by waiters and street people. This was a gimmick too far, both wildly anachronistic and painful to watch.

I have still not puzzled out what was symbolized by having both Mimi and Musetta wander through the garret before their actual entrances in Act IV—perhaps that they are always with Rudolfo and Marcelo even when they aren’t?—nor Musetta’s obvious pregnancy in the same act.

Vanessa Vasquez (Mimi) and Mario Chang (Rodolfo). Photo by Ken Howard.

As Mimi, soprano Vanessa Vasquez was a standout, bringing radiance and beauty to her voice in the early acts, and great expression when she is dying. If her coughing attacks seemed pasted into her interpretation, one cannot fault her vocal expression in the most poignant scenes. Her substantial voice soared easily, bloomed into striking moments of beauty, and became well controlled as she warmed into the role.

Mario Chang had some lovely, ringing high notes as Rodolfo. His voice shone in his duets with Mimi, but he was not consistent. Some entrances were a little rough, the occasional note hit too hard. Nevertheless, he was affecting throughout, and particularly through the Act III reconciliation duet with Mimi.

Zachary Nelson’s Marcello lacked passion. He sang pleasingly but seemed only intermittently engaged in the Act II and III quarrels with Musetta. The other Bohemians—Soloman Howard as Colline and Will Liverman as Schaunard—were solid and effective. Howard’s strong, robust voice could be more consistently controlled, but was used expressively for his “Overcoat” aria in Act IV. Schaunard’s jolly entrance in Act I, bearing money and food for his cold, starving garret-mates, was outstanding, bringing vocal warmth and good cheer to the stage.

I suggested earlier that Reyes as Musetta did not seem comfortable on skates. This must have affected her singing, which was a little cautious in Act II, but much stronger and more expressive in her fight with Marcello in Act III, and even when pregnant in Act IV. She was a solid Musetta who would be better without the skates.

Dale Travis hit all the conventional comic notes, first as the landlord Benoit in Act I and then as the hapless Alcindoro in Act II. Elliot Page was a clear-voiced Parpignol, offering his toys from above the doll houses of the miniature Paris.

# # # # #

Loved by opera aficionados but little known to the broader public, Bizet’s Pearl Fishers is a worthy work by any standards. Written several years before the composer’s final work, Carmen, it is filled with glorious melodies, striking choruses and instrumental numbers that point ahead to that masterpiece.

Santa Fe Opera’s Pearl Fishers, a revival of a production first seen in 2012, brought all of those the musical strengths to the fore. Conductor Timothy Myers elicited beautiful playing from the orchestra while finding all the dramatic high points in the score. The woodwinds in particular were noteworthy, with extraordinary solos from clarinet, flutes and horns.

Ilker Arcayürek (Nadir), Corinne Winters (Leila, veiled), Anthony Clark Evans (Zurga) with the Santa Fe Opera Chorus. Photo by Ken Howard for the Santa Fe Opera.

The choral scenes represent some of Bizet’s best music, anticipating the greats choruses of Carmen.They were powerfully sung, outlining the drama that sets the community of fisherfolk against the forbidden love between Leila, a priestess of Brahma, and Nadir, a hunter. Their liaison that interrupts Leila’s prayer vigil brings disaster on the village and leads to the opera’s dramatic, if unlikely, conclusion.

Pearl Fishers is one of those Romantic operas, along with such better known works as Madama Butterfly, Turandot and Aida, whose treatment of “exotic” subjects is problematic today. Pearl Fishers is supposedly set in Ceylon, although the locale was originally Mexico and the opera belongs authentically to neither locale.

Ceylon viewed through the frame of 19th-century Paris: Ilker Arcayürek (Nadir), Corinne Winters (Leila) and the Santa Fe Opera Chorus. Photo by Ken Howard.

Jean-Marc Puissant’s scenic design for the SFO stage deals with issues of cultural voyeurism in a creative way: the set features a massive picture frame, with everything beyond the frame representing a kind of generic “other” of stone temples and ruins, and everything in front representing the more specific milieu of 19th-century France. In other words, we see the setting through the frame of Bizet’s own time and place.

The stage direction of Shawna Lucey served the plot well. There were distancing elements of ritual that sometimes kept the chorus in front the frame, distracting from action farther upstage, but not to the point of interfering with the singers. She used the spaces onstage well, particularly in the scene when Leila and Nadir are discovered together inside the temple.

Corinne Winteres (Leila). Photo by Ken Howard.

Soprano Corinne Winters was a radiant Leila, her singing secure and bright, carrying easily over the orchestra in all of her biggest moments. Her Act III duet with Anthony Clark Evans’s Zurga, the leader of the fishers who is Nadir’s rival for her love, is one of the high points of the opera and the season. The rising arc of dramatic intensity is perfectly controlled, leading to a shattering climax. Equally memorable was her Act I aria and prayer at the beginning of her vigil.

Ilker Arcayürek has a light and delicate high tenor voice that is ideal for Nadir, but he struggled with the highest notes, easing into them or reaching for the tops of phrases. He was ardent in his declarations of love and expressive in the most dramatic moments of the opera.

Evans was a solid and forthright Zurga who occupied his critical role well. The best known piece from the opera, his Act I duet with Nadir, “Au fond de temple saint,” was as rousing as called for. In other scenes he was a convincing village leader whose jealousy of Nadir momentarily overcomes his love for Leila and affection for Nadir.

As Nourabad the high priest, Robert Pomakov used his powerful bass voice to dominate the scenes where he denounces Leila and Nadir, and calls for their execution. Elsewhere the character is a cipher, although Pomakov was reliably able in the role.

# # # # #

Danish composer Poul Ruders has written several operas on dark subjects—Kafka’s Trial, Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale and and Lars von Trier’s film Dancer in the Dark—but he wanted something different for his fifth opera. He turned to fairy tales, finding a little known story that fit his aim.

The Thirteenth Child, receiving its world premiere production at Santa Fe this summer, is based on a story by the brothers Grimm, and it takes Ruders in a different direction than those earlier works. The combination of fairy-tale magic, lightly comic moments and a happy ending have elicited a score marked with lyric elements, glowing, consonant orchestral interludes, generally light textures and one delightfully humorous male ensemble for the 12 older brothers of the title character.

David Leigh (King Hjarne) and Tamara Mumford (Queen Gertrude). Photo by Ken Howard.

Ruders was able to draw on a reservoir of dark and threatening orchestral music when needed, but that vein, so evident in his earlier work, is leavened by the lyrical writing. As presented in Santa Fe, The Thirteenth Child is an accomplished and entertaining work, a fitting achievement for a composer who describes opera as “an emotional affair wrapped in show biz.”

Not all the vocal music is graceful, however. The jagged lines, wide leaps and extreme ranges characteristic of many newer operas are used for emotive passages. Hjarne, the King of Frohagord, is one of the lowest bass roles in the repertoire, and the part of Drokan, the fairy tale’s requisite evil element of the plot, also lies very low, with sudden leaps into falsetto—executed with varying success—to symbolize madness.

I thought the best music in Thirteenth Child surrounded the moments of fairy-tale magic, and the orchestral interludes that set the emotional temperature for the ups and downs of the plot. Human emotions, so often the heart of opera, struck me as less effectively conveyed, particularly the intense moments when Ruders resorted to wide-leaping vocal lines that are hard to distinguish one from another.

Conductor Paul Daniel had the orchestra well in hand, shaping dynamics carefully to reflect the moments of tension and create an effective emotional profile. All of Ruders’s shifting moods, in response to the twists of the plot, were well delineated.

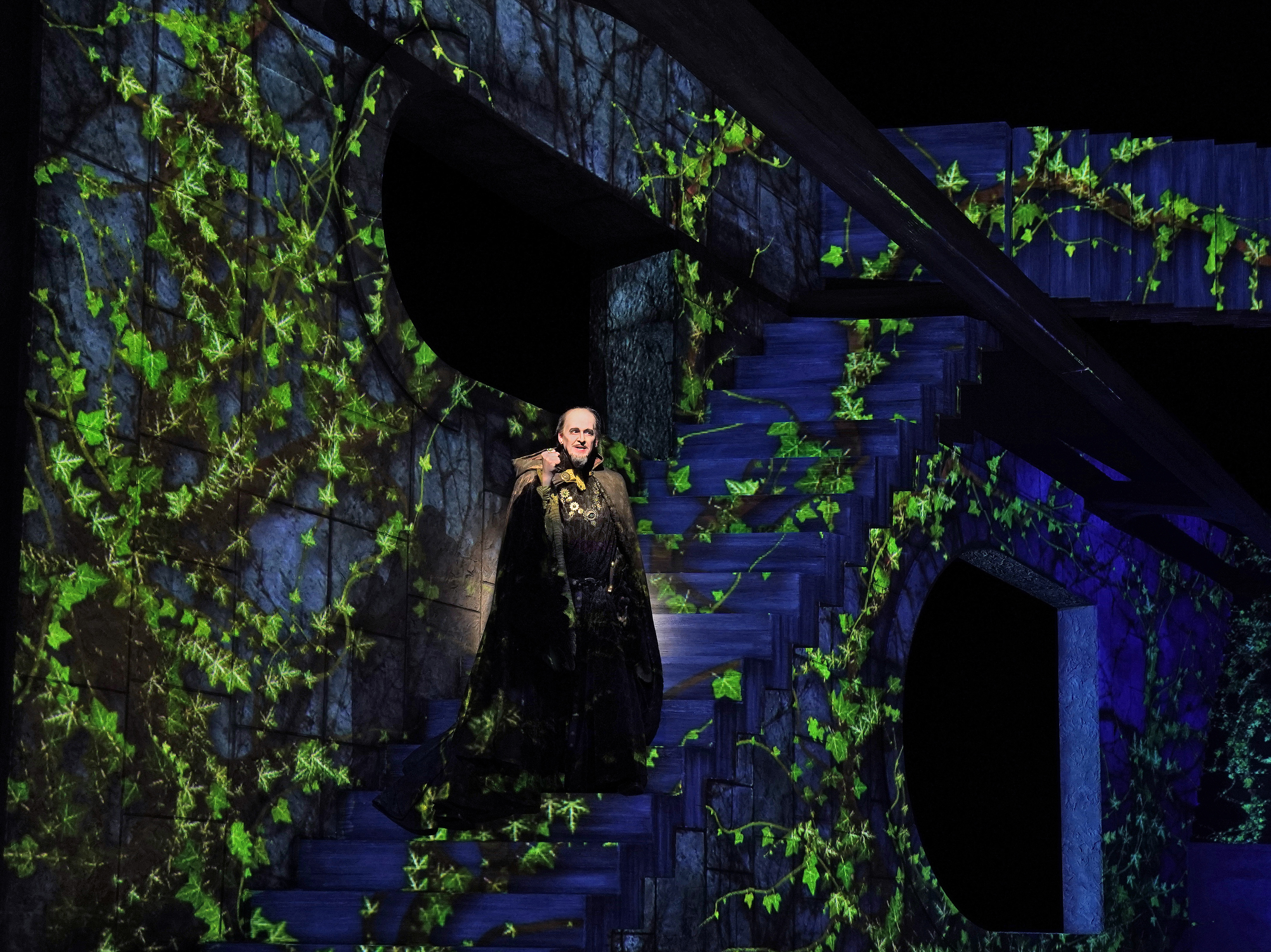

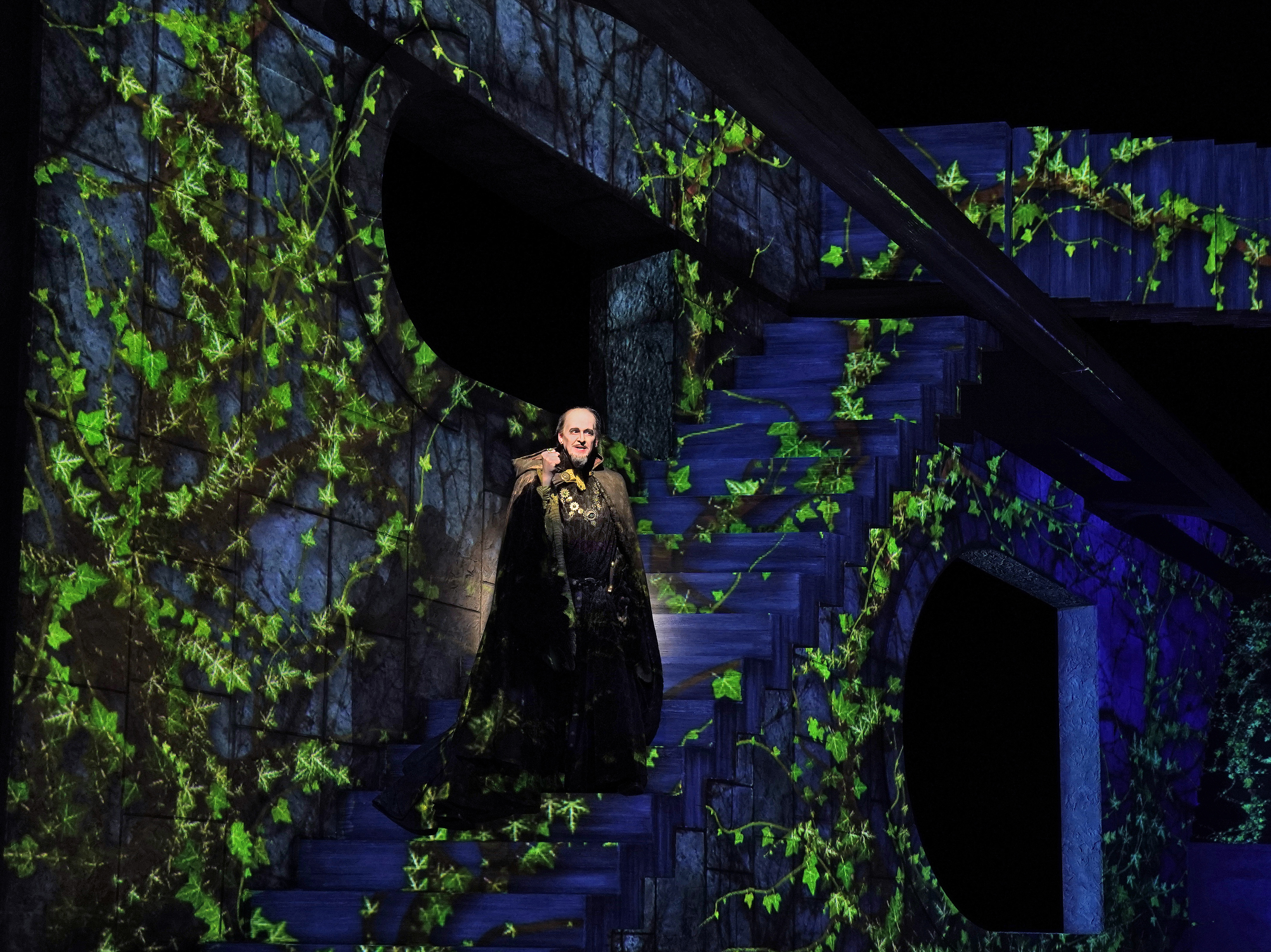

Alexander Dodge’s interesting unit set serves the opera well. The blank walls are used for engaging projections by Aaron Rhyme, including snakes when Drokan is plotting, ravens when the 12 brothers are turned to birds, and red flowers for the magical lilies that protect the kingdom of Frohagord. Other, less specific projections add sparkling beauty to several scenes.

The costumes by Rita Ryack are cinematic medieval on steroids—too much had the opera been realistic but just colorful and flamboyant enough for a fairy tale. My favorite visual effect was Hjarne’s funeral, with black-robed characters—nuns and monks?—with white collars and bright red spears held vertically. This is the best kind of spectacle.

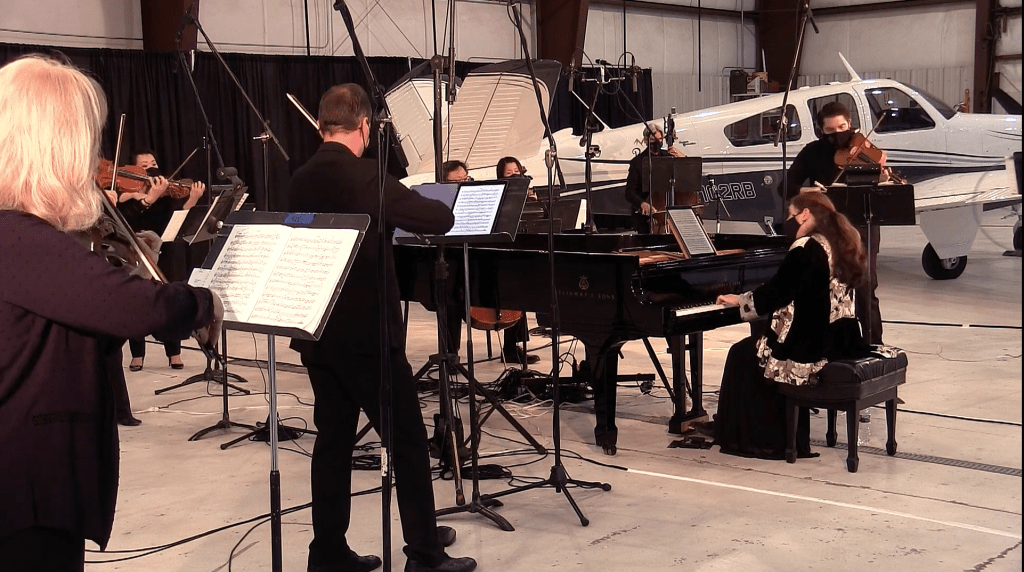

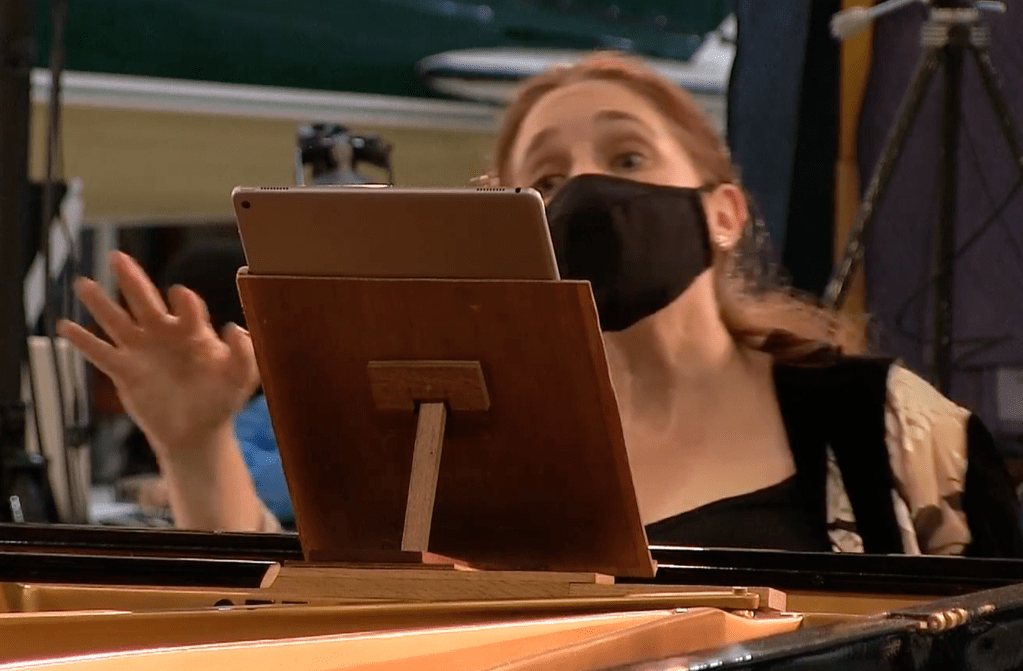

Bradley Galvin (Drokan) with elaborate projections. Photo by Ken Howard.

As Hjarne, David Leigh has the shortest time on stage—just the first scene—but his deep bass, clearly heard except for the very lowest notes, was solid and effective. He managed his leaps into falsetto and madness well, providing motivation for all that follows.

Hjarne is driven to obsession by Drokan, the truly evil element of the plot. As portrayed by Bradley Garvin, Drokan was the personification of scheming villainy, hoping to overturn Hjarne’s family, marry his daughter—the thirteenth child of the title—and rule Frohagord. He conveyed Drokan’s dark role in the plot through vocal timbre, ranging from subtle suggestions of evil to overt threat. So effective was he in the role that there was a smattering of applause at his demise.

Jessica Jones (Lyra). Photo by Ken Howard.

Tamara Mumford lent her rich, warm mezzo-soprano sound to Queen Gertrude, who is a guiding spirit to the story before and after her death. Critical to the first half of the opera, she was a steady presence dramatically and vocally outstanding. The spectral echoes and playback loops of her singing as a spirit are pretty conventional film and TV ghost effects, but reasonably effective in context.

As Lyra, the thirteenth child and heir of Hjarne, Jessica E. Jones was everything a fairy tale asks a princess to be: winsome, lovely and brave. Her bright and clear voice only complemented the portrayal.

Joshua Dennis as Frederic, who searched for Lyra for seven long years, successfully negotiated the leaps and twists of his challenging part, especially in his lengthy narration of his search. Apprentice artist Bille Bruley was appropriately sympathetic as Benjamin, the youngest of the 12 brothers. His voice was strong, and his diction unusually clear.

Jessica Jones (Lyra) and Bille Bruley (the dying Benjamin). Photo by Ken Howard.

Benjamin’s heroic death is the only real tragedy of the fairy tale, but it sets up the moral that is told at the end: “No joy without sorrow. . . . Dark days always come, in love we find the light.” This message has inspired Ruders to write an opera of expressive breadth and depth, one that I look forward to seeing and hearing again.

# # # # #

Santa Fe Opera. Photo by Robert Goodwin.

Tickets for the remaining performances in Santa Fe can be purchased through the calendar on the Santa Fe Opera Web page.

NOTE: This story was corrected 8.7.19. The Thirteenth Child is Poul Ruder’s fifth opera, not his sixth.