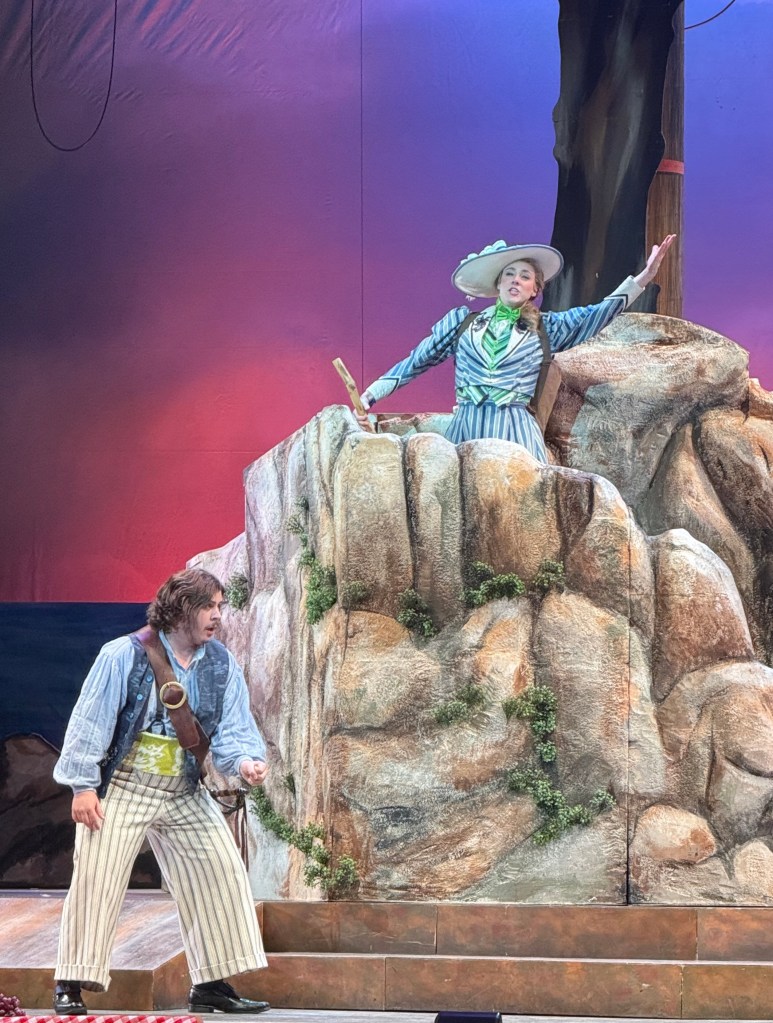

The perennially popular Pirates of Penzance puts in at Macky for the weekend

By Peter Alexander 10:40 p.m. March 12

CU’s Eklund Opera Program will present Gilbert and Sullivan’s hilarious Pirates of Penzance Friday through Sunday in Macky Auditorium (March 14–16; details below), and conductor Nicholas Carthy wants everyone to know what to expect.

“It’s a comedy,” he says. “This is not (Shakespeare’s) Henry V! It’s supposed to be ridiculous.”

And ridiculous it is, in some ways. If you don’t know the story, the callow youth Frederic has been apprenticed to a band of soft-hearted pirates through a confusion between a “pirate” and a ship’s “pilot.” He is bound until his 21st birthday, but because he was born on Feb. 29, that won’t happen until he is in his 80s.

Due to his exaggerated sense of duty, Frederic cheerfully agrees to remain with the pirate band for 60-plus more years, even though he has to postpone marriage to his true love Mabel, one of many wards of the pompous Major-General Stanley. After misadventures with the curiously ineffective pirates and the bumbling police, the day is saved when Frederic’s nursemaid Ruth reveals that the “pirates” are actually noblemen.

When they declare their loyalty to Queen Victoria, the way is cleared for Frederic and Mabel to marry.

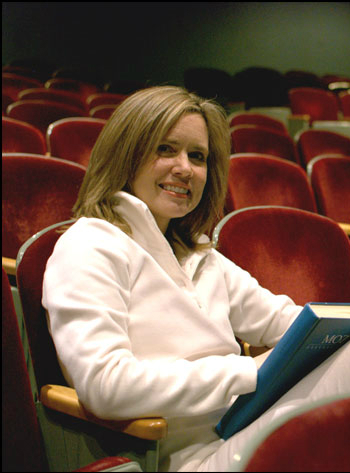

The CU production is stage directed by Leigh Holman, director of the Eklund Opera Program, with choreography by Laura Malpass. The production uses the same sets as previous CU performances in 2014, but with new costumes by Holly Jenkins Evans and new lighting design by Jonathan Dunkle.

“It will look different,” Holman says, “but in terms of interpretation, we took the same approach as last time. There are many different levels where the show can entertain. There are Gilbert & Sullivan fans that know all the intricacies, and there are people that will learn it as they’re sitting there. Other people will see the slapstick, and they’ll enjoy it too.”

The show must have wide appeal, since it has been selling exceptionally well. According to Holman, “the last show that reached this (many) ticket sales was West Side Story.”

There are several specific aspects of Pirates that Holman and Carthy hopes the audience will recognize. For one, there are clues that the pirates are really from the upper class. For one, “they’re drinking sherry at the beginning,” Carthy says. “If they were real pirates they would be drinking rum.”

At the same time, there is sharp satire of the upper classes. As Carthy puts it, the performers are “having a nod and a wink at the audience, saying, ‘we know what these people are like, and you do too, don’t you?’ Both the audience and the people onstage are in on the joke.”

That pointed satire explains why Gilbert’s text was not popular with the Queen and nobility, even though Sullivan’s music was. “These little barbs against royalty were what Queen Victoria disapproved of,” Carthy says, “which is why Sullivan got knighthood and Gilbert didn’t.”

In one example, the Pirate King, himself a noble, takes a particularly brutal jab at the rigidly “respectable” upper classes. Speaking of piracy, he says, “I don’t think much of our trade, but compared with respectability, it is relatively honest.”

Satire of the upper classes appears in all cultures. It is central to much British literature, but also dates from Roman and Greek theater into the 20th-century. “Gilbert and Sullivan’s policemen are exactly the same as Monty Python’s policemen,” Carthy says. “They are of a particular class and accent—that is a thread through the ages.”

It is also important to know that Sullivan aimed higher than writing popular potboilers. “Sullivan wanted to be a serious composer and ended up hating Gilbert,” Carthy says. “He wanted to stop (working with Gilbert), but then he lost money in a market crash and had to sign on for another five years.”

Musical evidence of Sullivan’s aspirations is found in throughout the show. “There are little bits of Sullivan as a serious composer, and not just this sort of thing, that we remember him for,” Carthy says, singing an oom-pah accompaniment.

In some places, there are even traces of serious opera, including hints of Donizetti and Rossini. Holman finds these passages especially expressive. “The love duet (between Mabel and Frederic) is beautiful,” she says. “It’s the most sincere thing in the show. That piece is just gorgeous.”

She also hopes you will notice the choreography. “It’s a beast to choreograph, with so much movement,” she says. “Malpass has taken predominantly non-dancers and done amazing jobs with them. (In this show), there’s always something to see, lots of physicality (as well as) great singing!”

Carthy admits that Pirates does not always conform to modern sensibilities. “It’s a piece of its age,” he says. But he believes its comedy is universal, transcending Victorian sensibilities. “It’s quirky but it works, and it suggests a little depth,” he says.

“Above all, it knows what its audience wants.”

# # # # #

University of Colorado Eklund Opera

Leigh Holman, stage director; Nicholas Carthy, conductor

- W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan: The Pirates of Penzance

7:30 p.m. Friday, March 14, and Saturday, March 15

2 p.m. Sunday, March 16

Macky Auditorium

NOTE: The spelling of Eklund Opera was corrected March 13. The original story incorrectly had the spelling as Ecklund.