Artistic Director Evanne Browne conducts her last program with Seicento

By Peter Alexander April 24 at 6:20 p.m.

Evanne Browne, the first and the fourth director of Boulder’s Seicento Baroque Ensemble, will perform some of her favorite music for her last performances with the group, Friday through Sunday in Denver, Boulder and Longmont (April 26–28; details below).

Browne has announced that she will retire as Seicento’s artistic director following the concerts, which mark the end of the ensemble’s current season. A search is under way for her successor.

Browne founded Seicento in 2011 then left the group when she moved to the east coast in 2017. Two conductors later, she returned to Colorado, and has led the group for the past two years. She says the program was planned in advance and not specifically chosen for her last concert with Seicento. It might well have been, though, as the early years of the Baroque are Browne’s specialty.

“This is the era that I truly love—the early Italian Baroque,” she says. “This program is a passion of mine (and) was my specialty in my performing years.”

The music she is referring to comes from the period around 1600. The music of the Renaissance had mostly been written for choirs, but starting around 1600 music was written for solo singers with accompaniment of a bass line and simple chords played by keyboard or other stringed instruments. The emphasis in the solo singing was on expression of the text, with vocal lines that required extensive ornamentation.

“It is very virtuosic,” Browne explains. “It really is an approach that where, you have to fill in the blanks.”

To help promote understanding of the style, Browne has been working with four apprentice artists who will be featured on the program, sopranos Ann Jeffers and Andrea Weidemann, and mezzo-sopranos Emily Anderson and Gabrielle Razafinjatovo.

“I’ve done a lot of that kind of music as a soloist,” Browne says. “It is very virtuosic, and my goal in having the apprentice artists program (was) to pass that knowledge on.”

Because much of the expression in the early Baroque was supplied by ornaments that were not written out, that was where Browne started with the apprentice artists. She started by teaching the most common ornaments, and suggested recordings they should listen to. “They learned the cadential ornaments [for endings of phrases],” she explains. “Then we started filling in thirds, and filling in fourths, and it was so much fun to see them go, ‘Oh!’”

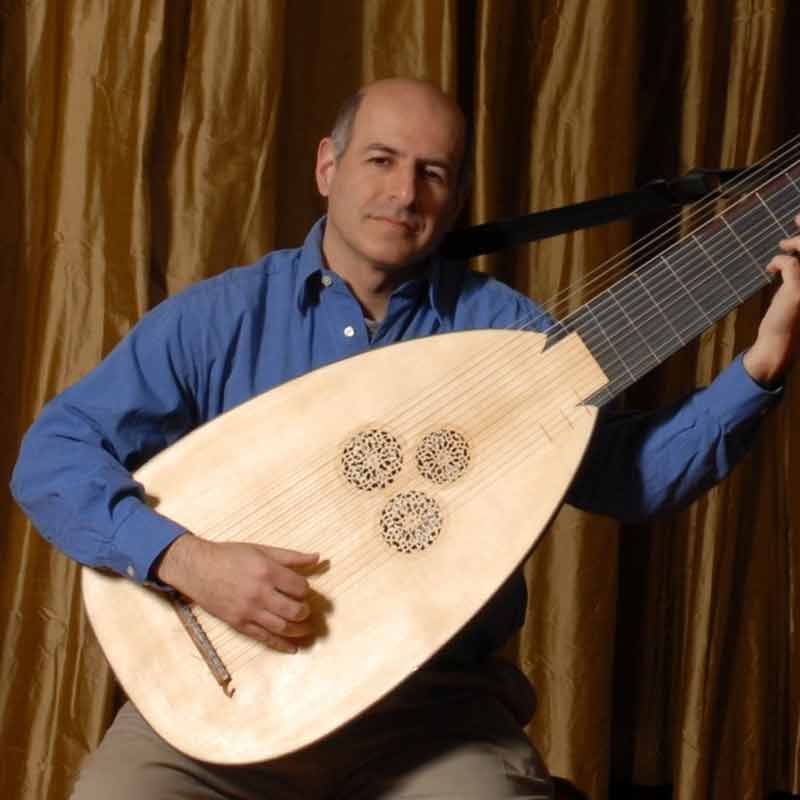

To make an interesting program for both solo artists and the Seciento chorus, Browne selected both solo pieces in a style called “monody”—ornamented solo voice with continuo accompaniment that will be sung by the apprentice artists—and music from the period for the full chorus, including madrigals and a mass setting by Frescobaldi. There are also instrumental pieces played by local performers on Baroque instruments and three guest artists—William Simms on theorbo (a large stringed lute that can play chordal accompaniments), Chuck Colburn on cornetto (a fingered wind instrument with a trumpet-like mouthpiece), and Webb Wiggins on harpsichord.

Browne singles out two portions of the program that bring together the Seicento chorus and the other performers. “Things that I think are spectacular are our set of variations on a tune, sometimes called ‘La Monica’,” she says. “This tune is anonymous, (and) appears in the early 1500s. It appears in France, it appears in Italy, it appears in England, and different composers take that same tune and set it for different instruments.”

The set is based around music by Frescobaldi that incorporates the tune within a choral mass. Seicento’s set begins with a unison performance of the tune, followed by the mass with different instrumental versions of the tune interspersed between the movements. “The Mass is gorgeous, it’s a double choir mass,“ Browne says.

Between movements, she explains, “William Simms is going to play variations on theorbo that were written by Piccini, our cornet player is going to do ornamentation on his own that shows what a performer would have done at the time, and then the violins have a Sonata by Marini that’s also a set of variations. I love this set!”

The final piece on the program, Venga dal ciel migliore (Come from the best heaven) by Giovanni Rovetta, also brings performers together. “That’s a highlight for me because it brings the violins and the soloists and the choir and all the continuo instruments (together), and the cornetto player’s going to be playing.

“It’s from that transitional time when a piece of music has choral sections that are punctuated by solo sections. The solo sections have all of the ornamentation, a lot of written out runs, and very challenging technical parts, and then the choir comes in and kind of repeats what they said.”

Browne emphasizes how the musical changes at the beginning of the Italian Baroque are still familiar to us today. “We’ve been calling this kind of a revolution in music,” she says. “This is when we change to the melody accompanied by harmonies, which is a big change from Renaissance music.”

Ultimately, the importance of the “revolution” was in creating a texture and style of music that continues to this day. In fact, any time you turn on the radio you will hear a melody accompanied by harmonies, in popular songs, in jazz, in show tunes—almost anything you hear today,

As Browne wrote in her press release, “A lead melody supported by harmony and a prominent bass line is still the primary format of today’s music, from classical to jazz to rock and roll.”

And it all started around 1600.

# # # # #

“Prima Melodia: Birth of Baroque”

Seicento Baroque Ensemble, Evanne Browne, conductor

With sopranos Ann Jeffers and Andrea Weidemann, and mezzo-sopranos Emily Anderson and Gabrielle Razafinjatovo, Seicento apprentice artists.

William Simms, theorbo, Chuck Colburn, cornetto, and Webb Wiggins, harpsichord, guest artists

- Monteverdi: Movete al mio bel suon

- Sigismondo d’India: Cruda Amarilli

- Cipriano de Rore: Ancor che col partire

- Riccardo Rognoni: Ancor che col partire

- Alessandro Grandi: Laetamini vos o caeli

- Monteverdi: Quel sguardo sdegnosetto

- Francesca Caccini: Maria, dolce Maria

- Monteverdi: O come sei gentile

- Girolamo Frescobaldi: Toccata Settima in D minor, Book 2

Variations on a Melody: “Aria della Monica”:

- Anonymous: Madre, non mi far monaca (unison)

- Frescobaldi: “Kyrie” from Missa sopra l’aria della Monica (chorus)

- Alessandro Piccinini: Corrente sopra l’Alemana (theorbo)

- Frescobaldi: “Gloria” from Missa sopra l’aria della Monica

- Une jeune fillette (embellishments improvised on cornetto)

- Frescobaldi: “Sanctus” and “Agnus Dei” from Missa sopra l’aria della Monica

- Biagio Marini: “Sonata sopra la Monaca” (two violins and continuo)

- Luzzasco Luzzaschi: Toccata in e minor

- —O dolcezz’ amarissime d’amore

- Giulio Caccini: Amor, io parto

- Nicolò Corradini: Spargite flores

- Giovanni Rovetta: Venga dal ciel migliore

7:30 p.m. Friday, April 26, St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, Denver

7:30 p.m. Saturday, April 27, Mountain View Methodist Church, Boulder

3 p.m. Sunday, April 28, United Church of Christ, Longmont

TICKETS, including live stream of Friday’s performance