MIssa Solemnis, “Magnum Opus” of great extent and significance, May 4

By Peter Alexander April 30 at 5:50 p.m.

Beethoven was a few years years late.

He promised his friend, pupil and patron Archduke Rudolf that he would write a solemn mass—Missa Solemnis—for the latter’s investiture in 1820 as the Archbishop of Olomouc. But the massive score was not finished in time. In fact, it was not performed until April 7, 1824—in St. Petersburg, under the sponsorship of another of Beethoven’s patrons, Russian Prince Gallitsin.

The size of the work, which takes 80 minutes to perform, and the difficulty of the choral parts remain obstacles to performances. So it is a noteworthy event that the Boulder Philharmonic and Boulder Chorale will join forces to present the Missa Solemnis Sunday at Macky Auditorium (4 p.m. May 3; details below).

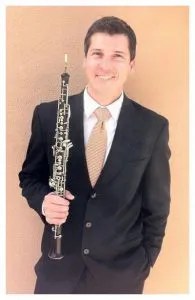

Michael Butterman, music director of the Boulder Phil, will conduct. The full 130-member Boulder Chorale has been rehearsed by director Vicki Burrichter. Soloists will be Tess Altiveros, soprano; Abigail Nims, mezzo soprano; Kameron Lopreore, tenor; and Pectin Chen, bass.

This is the first time either Butterman or Burrichter have presented the work. “I have personally wanted to do it for years and years,” Butterman says. “It’s a huge lift for (the chorus), so you have to have a partner that is up to it and is willing to take it on.

“I’ve been in touch with Vicki at the Boulder Chorale through the years, and this came up when she and I were talking. She said ‘I think we can do it. I want to do it!’”

For her part, Burrichter says that the Chorale is now ready for the challenge. “I wouldn’t have done this piece with them even five years ago,” she says, “but they are now at a place where they are very highly trained up. This is my 10th year with the Chorale, and we’ve been working very hard to get to an even higher level than when I started.”

Several aspects of the music present challenges to the chorus. They sing almost nonstop, with no breaks for solo arias or duets. Their parts cover a wide range from very high to low, with difficult, angular melody lines. The fugues are often difficult to sing, especially when each part has to project the theme independently of the others.

Burrichter identifies other challenges as well. “Yes, the tessituras (voice ranges) are high, especially for the sopranos,” she says. “But the constant change in dynamics (loud to very soft and vice versa) is probably the hardest thing. You have to always look ahead. I think also the hardest thing is getting the flow of the piece, because it is dramatically different from Bach or Mozart. Understanding why (Beethoven) wrote what he did, what he was trying to say—those are things that take a long time (for the singers) to integrate.”

“It is one of the most daunting works that I’ve ever put my mind to,” Butterman says. “I’m truly humbled by this piece. It seems so incredibly detailed, so dense, so masterful that I’m really in awe of this—written by someone who was probably profoundly deaf. It’s just staggering. The contrapuntal mastery that he displays over and over again, throughout the work, is astonishing.”

The use of counterpoint shows that Beethoven knew the traditions established in the mass settings by earlier composers. Other traditional gestures that he incorporated into the score include the use of fugue for certain texts, starting the Gloria with ascending joyful lines in the chorus, the use of traditional church modes, and the use of solo flute to represent the Holy Spirit.

In other ways Beethoven added his own original ideas. One that is particularly powerful is the insertion of trumpets and drums suggesting military music right before the text Dona nobis pacem (Give us peace). Beethoven lived during a time of extended warfare across Europe, including the occupation of Vienna by French troops, giving the plea for peace special force.

Burrichter sees a relevance for that passage still. “Listen to how Beethoven changes the Dona nobis pacem, and how this relates to what’s happening in the world right now,” she says. “The message that Beethoven was trying to send in 1827 is just as relevant today.”

She also says “I think this piece has an unfair reputation as unsingable and an assault on the senses. What great composers do is demand great things of singers and instrumentalists. Beethoven was reaching for transcendence.”

She advises the audience to “enter into the experience that Beethoven is trying to create. Enter into Beethoven’s world in the same way that you would one of his symphonies.”

But the last word on the Missa Solemnis should go to the composer. On the copy that he presented to his pupil and friend the Archbishop, Beethoven wrote “Von Herzen—Möge es wieder—Zu Herzen gehn!”

“From the heart—may it return to the heart!”

# # # # #

“Beethoven’s Magnum Opus”

Boulder Philharmonic, Michael Butterman conductor

With the Boulder Chorale, Vicki Burrichter, director

Tess Altiveros, soprano; Abigail Nims, mezzo soprano; Kameron Lopreore, tenor; and Pectin Chen, bass

- Beethoven: Missa Solemnis, op. 123

4 p.m. Sunday, May 4, Macky Auditorium