Programs are filled with music of defiance, resistance and remembrance, May 14–18

By Peter Alexander May 12 at 8:08 p.m.

It all starts with the symphony.

Every year, the Colorado MahlerFest presents one of the symphonic works of composer Gustav Mahler—one of the ten symphonies, or another large-scale symphonic work such as the Lied von der Erde (Song of the earth). For the 38th MahlerFest taking place this week (May 14–18; see programs and other details below), that central work is the Symphony No. 6 in A minor. According to MahlerFest artistic director Kenneth Woods, everything else on the program is chosen to harmonize with the symphony.

“It always starts with the Mahler symphony,” Woods says. “Mahler’s Sixth is his only tragic symphony—it’s the only one that ends in a minor key. His late works end slowly and softly, (but) they end with some hint of consolation, where the end of the Sixth is totally and utterly bleak.

The final movement famously includes “hammer blows”—explosive thuds that represent the blows of fate. These loud, dull sounds are traditionally related to events in Mahler’s life: the death of his oldest daughter, the diagnosis of the heart condition that would hasten his death at age 50, and his dismissal from the Vienna State Opera.

The hammer blows are unique in the symphonic repertoire, and getting the right combination of loud and dull is tricky. Most orchestras have their own custom-made “Mahler Boxes” for the Sixth. They are usually a wooden box that is struck dramatically by a percussionist with a large wooden hammer.

Mahler contemplated as many as five hammer blows. Some scores include three, the same number as the blows in Mahler’s life. But in the end, Mahler settled on two, perhaps feeling that the third blow was symbolically fatal and should be avoided.

Performances vary, but MahlerFest will include only two. “His final decision was two hammer blows,” Woods says. “Maybe in a more pessimistic era you want to include more, but we decided to do what he wrote, rather than us decide what’s best.”

For Woods, the hammer blows and the bleak ending make the Sixth Symphony even more heroic. “These hammer blows announce the inevitability of destruction and defeat, but the hero fights on ever more bravely,” he says.

He explains the symphony’s ultimate meaning with a pop culture analogy from the film Saving Private Ryan. “When Tom Hanks’s character has finally found Private Ryan, he’s dying and he says to Ryan, ‘earn this.’ I think Mahler’s Sixth is not far away from that in spirit. Mahler takes us through the life of a character who is fighting for a better world—not because he’s going to benefit from it, but we might.

The music that Woods selected for other programs come out of times of struggle and suffering. The titles of the individual programs—“Songs of Protest and Defiance,” “Determination and Defiance”—reflect that perspective. Many of the pieces directly reflect their composer’s experience during the violence of the 20th century, especially the two world wars.

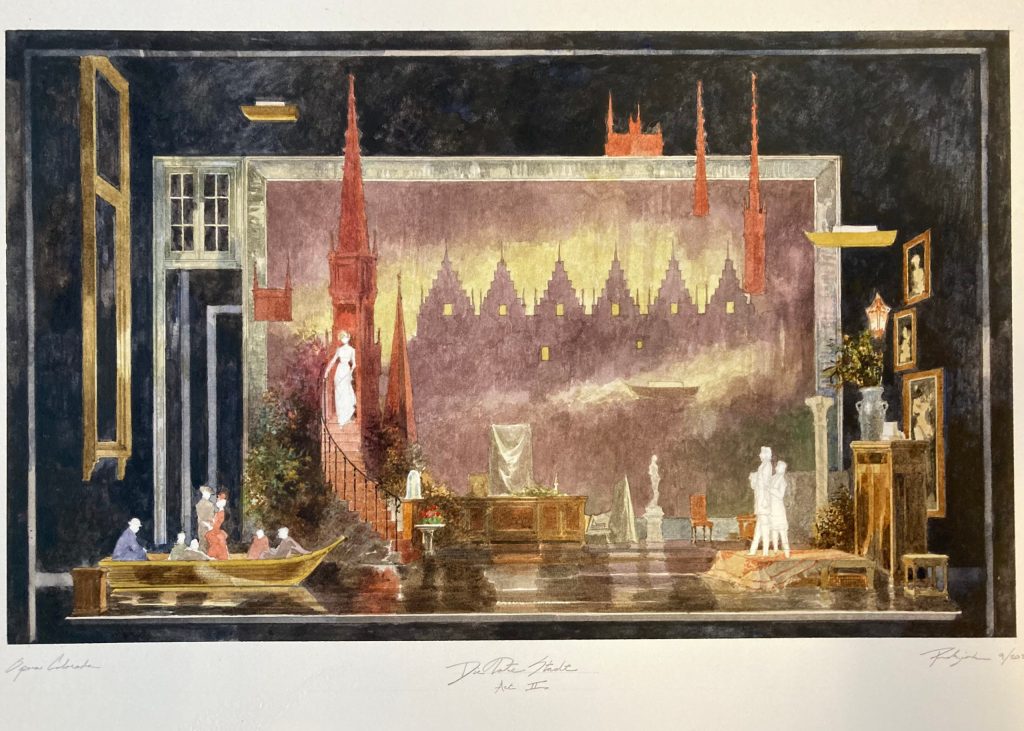

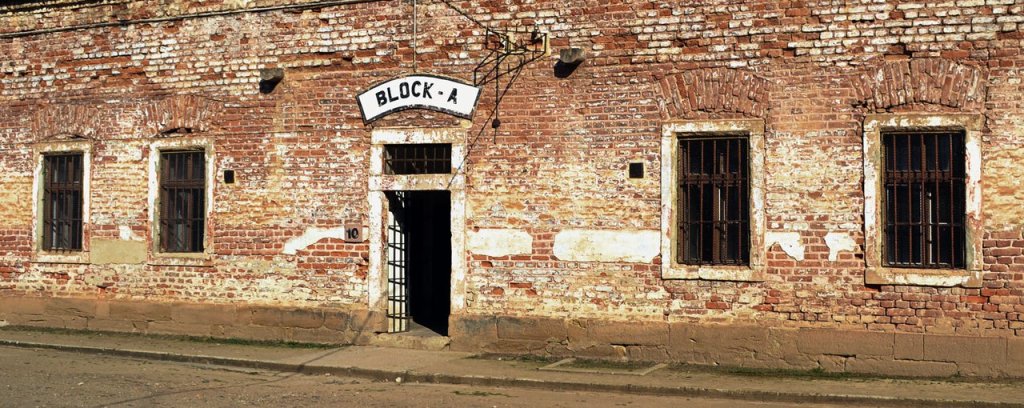

The festival’s opening night performance Wednesday (7:30 p.m. May 14 at Mountain View United Methodist Church) will present a piece actually written in the Terezín concentration camp in Austria during World War II. Although it was rehearsed in 1944, the Nazi authorities did not allow its performance, and both the composer, Viktor Ullmann, and the librettist, Peter Kien, were murdered at Auschwitz.

Titled Der Kaiser von Atlantis, oder Die Tod-Verweigerung (The Emperor of Atlantis, or The disobedience of death), it is a one-act opera about a power-mad dictator, Kaiser Überall (Emperor Overall) and Death, an overworked soldier who goes on strike. A biting, cynical piece, with the Kaiser an obvious satire of Hitler, it was a courageous statement during wartime.

“Here you have Ullmann in a camp, knowing he’s destined for Auschwitz,” Woods says. “His response was not to say, ‘oh, well,’ but to write incredibly sharp, multi-layered political satire. And dare I say, give the finger to Hitler, who was the model for the Kaiser. Ullmann is a challenge to us, because if he can set a story (mocking) Hitler in a concentration camp, then we shouldn’t feel like we can’t express ourselves directly, about music, or politics, or society.”

Other works during the festival are worthy of attention. On the chamber music program “Determination and Defiance” (7 p.m. May 16 at the Roots Music Project), Erwin Schulhoff was a greatly gifted and widely recognized composer who emerged from serving in World War I with deep emotional scars. “Schulhoff is a particularly poignant case because the music is really touched by genius,” Woods says.

“Everything I’ve done of his has been a huge discovery. Some of his stuff is biting, satirical, some of it is angular, and the Sextet is a tumultuous, fiery piece.”

On the same chamber program, Shostakovich’s Seventh String Quartet was written in 1959–60, at a particularly difficult time in the composer’s life. “To me, the Shostakovich (String Quartet) is an expression of what it is like to see the clouds on the horizon,” Woods says. “He’s hinting at a world of threats and shadows and whispers.”

Saturday’s orchestral program (7:30 p.m. May 17 in Macky Auditorium) features the Symphony in F-sharp by Erich Wolfgang Korngold, whose career was shaped by World War II. “That’s a fantastic work,” Woods says. “Korngold became a hugely successful opera and concert music composer, and when Hitler came to power, he had to flee.”

Korngold came to the U.S. in 1934. He moved to Hollywood, where he was a film composer, virtually inventing the modern film score in such films as Captain Blood, The Sea Hawk and The Adventures of Robin Hood.

“He felt that he could not write music for the concert hall as long as Hitler was alive,” Woods explains. “Following World War II he began to return to the concert hall. In 1948 he wrote his one and only symphony, which does seem to trace a historical arc of those difficult years.

“We’ve got a first movement that’s very forbidding and violent, a second movement that seems full of frantic activity, then a mournful, soulful adagio like a great lament for the losses of the war, and a finale that is a celebration of peace.”

Finally, Woods singles out the two works on the culminating Sunday concert with the Mahler Sixth (3 p.m. May 18 in Macky Auditorium), Bohuslav Martinů’s Memorial to Lidice and Dismal Swamp by American composer William Grant Still. “On one level (Dismal Swamp) is about the actual Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia, quite a forbidding one,“ Woods says. “But it becomes a pathway to freedom for enslaved people during the Civil War.”

One of the most direct and poignant expressions of loss and resistance is Memorial to Lidice by the Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů. In June, 1942, the Nazis obliterated Lidice, a small Czech village outside Prague, in retaliation for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, one of the most cruel overseers of the Holocaust. All the men of Lidice were killed, the women and children sent to concentration camps, and the town burned to the ground.

Martinů, who was living in the U.S. heard of the atrocity and wrote an orchestral memorial to the town. “It’s an amazing work,” Woods says.

“You might ask why Martinů thought writing a short piece for orchestra was going to make any difference in the middle of a world war, but the piece has outlived Hitler. (Martinů thought) I’m going to do it because it’s the right thing to do.

“I’m going to write a piece about this atrocity so at least I did something to commemorate it.”

# # # # #

Colorado MahlerFest XXXVIII

“Defiance, Protest, Remembrance”

Kenneth Woods, artistic director

FULL SCHEDULE of all MahlerFest XXXVIII events HERE

Musical Performances:

Wednesday, May 14

“Death Goes on Strike”

Colorado MahlerFest Chamber Orchestra, Kenneth Woods, conductor

- Viktor Ullmann: Der Kaiser von Atlantis, oder Die Tod-Verweigerung (The emperor of Atlantis, or The disobedience of death)

7:30 p.m., Mountain View United Methodist Church, Boulder

Thursday, May 15

Songs of Protest and Defiance

Jennifer Hayghe, piano, with Alice Del Simone, soprano; Hannah Benson, mezzo-soprano; Brennen Guillory, tenor; Andrew Konopak, baritone; Ryan Hugh Ross, baritone; and Gustav Andreassen, bass;.

- Mahler: “Revelge” (Reveille)

- Philip Sawyers: Songs of Loss and Regret

- Mahler: “Der Tamboursg’sell” (The drummer boy)

—“Wo die schönen Trompeten blasen” (Where the fair trumpets sound) - Schubert: “Kriegers Ahnung” (Warrior’s foreboding)

- Shostakovich: “Réponse des Cosaques Zaporogues au Sultan de Constantinople”

- (Response of the Zaporozhian cossacks to the sultan of Constantinople) from Symphony No. 14

- Mahler: “Lob des hohen Verstandes” (Praise of lofty intellect)

- Spirituals and protest songs TBD

3 p.m., Canyon Theater, Boulder Public Library

Free and open to the public

Friday, May 16

“Determination and Defiance”

MahlerFest chamber music ensembles

- Gwyneth Walker: “Raise the Roof!”

- Kevin McKee: “Escape”

- Ernst Bloch: Suite No. 3 for Solo Cello

- Shostakovich: String Quartet No. 7 in F-sharp minor, op. 108

- Erwin Schulhoff: String Sextet

7 p.m., Roots Music Project, 4747 Pearl St., Suite V3A

“Rhythm, Roots & Resonance”

Jones/Butterfield Duo

9 p.m., Roots Music Project

Saturday, May 17

“Celebrating Peace”

Mahlerfest Festival Orchestra, Kenneth Woods, conductor

With Daniel Kelly trumpet

- Mahler: Todtenfeier

- Deborah Pritchard: Seven Halts on the Somme, Concerto for Trumpet and Strings

- Erich Wolfgang Korngold: Symphony in F-sharp, op. 40

7:30 p.m., Macky Auditorium

Sunday, May 18

“Resistance”

Stan Ruttenberg Memorial Concert

Mahlerfest Orchestra, Kenneth Woods, conductor|

With Leah Claiborne, piano

- Bohuslav Martinů: Memorial to Lidice

- William Grant Still: Dismal Swamp

- Mahler: Symphony No. 6 in A minor

3:30 p.m., Macky Auditorium

TICKETS for all ticketed events in MahlerFest XXXVIII may be purchased HERE.