Santa Fe Opera continues its exploration of Wagner’s music dramas

By Peter Alexander Aug. 11 at 5:35 p.m.

Editor’s Note: This is one of several posts covering four of the five operas presented this year at the Santa Fe Opera.

Die Walküre, the last of the Santa Fe Opera productions I saw this summer (Aug. 8), continues the company’s exploration of Wagner’s music dramas, following the 2022 production of Tristan und Isolde previously reviewed here.

for the Santa Fe Opera

The performance was marked by excellent singing, flexible but ultimately meaningless settings, and costumes that ranged from impressive to silly. The stage direction was busy, filled with ideas but no overriding concept.

Many operas today are time shifted; I have reviewed several of these at Santa Fe in the past (La Traviata and Don Giovanni, Rosenkavalier and L’elisir d’amore, Tosca). Die Walküre, based in legend, has no set era, but Santa Fe’s current production proposes many different historical time slots for the story. The opening act took place in an abstract space filled with 1950s appliances, Sieglinde wore a contemporary dress, Brünnhilde was clad in generic old-norse gear, and the Valkyries wore different military uniforms from across the globe and representing the middle ages to the 20th century.

The set remained abstract throughout—two horizontal panels filled with vertical, elastic cables that characters reach and enter through, that meet mid-stage to open or close as the staging requires. These panels are topped by a walkway with a railing of entangled red ropes, a symbol used throughout to represent marriage—literal ”ties that bind”—as enforced by Fricka. The upper walkway is used by Wotan, Fricka and others, as a viewpoint on the stage action below. As a setting, this is suggestive of nothing at all.

Various non-singing characters appear throughout. There are mysterious figures in black body suits who enter and leave the stage, handle Siegmund’s sword, Brünnhilde’s shield, and move set pieces around. There are actors representing Alberich, who is referred to but not present in the plot; Grimhilde, the Gibichung who will be mother to Alberich’s son Hagen later in the story; Erda, Siegmund’s, Sieglinde’s and the Valkyries’ earth-spirit mother; and other shadowy figures from Ring mythology.

None of this clarifies the plot. Clearly, director Melly Still has many ideas about how to present Die Walküre within the Ring Cycle, but her disparate ideas do not add up. At it’s core Die Walküre tells a simple story—Siegmund runs off with his sister Sieglinde and they conceive a child; Sieglinde’s betrayed husband Hunding tracks them down and kills Siegmund.

But there is no story so simple that Wagner and stage directors cannot make it more complicated, which is what happens in Santa Fe. Wagner’s role, having written the libretto based on the Nordic myths, lies with meddling gods and magical weapons.

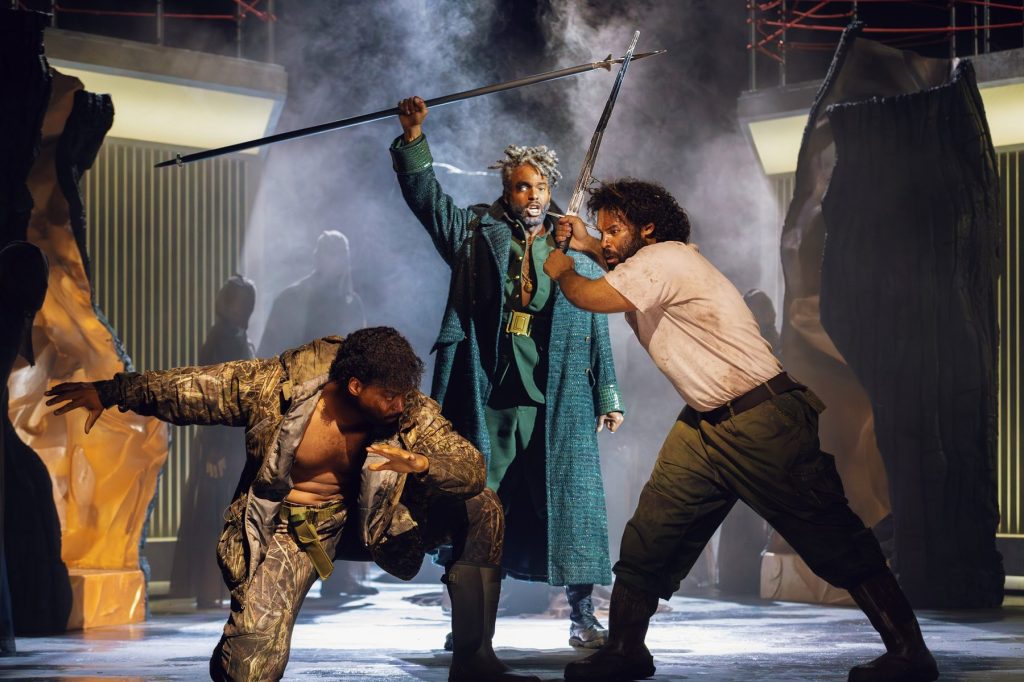

The stage director takes credit for the rest, starting with the black-clad figures, who only obfuscate the plot. While the basic action is clear, one is distracted by dark figures posing mysteriously behind the elastic bands, reaching through them, entering and leaving the stage, handling props. There is broader symbolism at work, but none of this helps to tell the story of Die Walküre. Another intrusion that seemed gratuitous was Wotan’s cadre of “enforcers,” military police characters dressed like Star Wars extras or World War I impersonators.

One moment in particular stands out as a missed opportunity. The first act ends with the walls of Hunding’s hut flying open and spring bursting over the twins/lovers Sieglinde and Siegmund, blessing—as Wotan later argues to Fricka—their incestuous love. Wagner’s music is powerful, soaring and blooming. It is expressing something that needs to be shown. But in Santa Fe, the panels open up and the lovers occupy a bare space on the stage. Of spring there is not the slightest visual sign.

In the role of Siegmund, Jamez McCorkle reached all of his notes, sang with strong feeling, but allowed a slight bleat enter his voice at crucial moments. This rough edge pushed his voice out, but as often with strained Wagner singers, it did not add beauty to the sound.

Vida Miknevičiūtė portrayed a slight Sieglinde, vulnerable and frightened by her rising feelings. Although light for Wagner, her voice was precise, employed carefully, only occasionally a little wobbly. She sang forcefully through the love duet with Siegmund, rising to steely heights, and melting into her gentler moments.

As Wotan, Ryan Speedo Green was struggling with altitude, or the dry mountain air, or both. While onstage he was handed water through the elastic bands in both acts II and III, and his voice sounded worn by the end of each act. At his best, he was a gruff, confrontational Wotan, consumed by his growing anger at being caught in his own trap. He easily commanded the stage in every appearance. Whatever his struggle, it did not diminish his presence.

Tamara Wilson’s entrance as Brünnhilde was greeted with cheers. She was a solid member of the cast, singing with force and power, if not quite dominance. Her interactions with Green’s Wotan near the end was a forceful turning point, in both the opera and for the cycle beyond Walküre.

Sarah Saturnino provided a secure vocal element as Fricka. Her long Act II argument with Wotan—for me one of the most interesting portions of a long evening—was deeply engaging. Saturnino sang with genuine depth and expression.

Solomon Howard brought his big, resonant bass voice to the role of Hunding, filling the house with strong tones. His military-fatigue costuming lent an appropriately menacing air, although I hard a hard time getting past his resemblance to Jimi Hendrix. Contemporary costuming has its perils.

The Valkyrie’s calls rang resoundingly over the orchestra, calling their warrior band together. All were potent contributors to the performance. With Brünnhilde, they displayed an infectious joy of companionship. James Gaffigan conducted with a sure hand, leading a performance steeped in experience and understanding of the score. The orchestra, and especially the expanded brass section so crucial to Wagner, played tirelessly over the music drama’s long duration, providing powerful heights as well as more intimate moments of sensitivity.

The Aug. 8 audience I take to have been about 75% Wagnerphiles—two gentlemen in front of me wore horned helmets of felt—who loved every minute of Wagner’s music. They know the story backwards and forwards, and so could recognize all the references and the crucial turns of the plot. They deservedly cheered the singers.

For those less familiar with the story, it must at times have been a mystery.

Die Walküre will be repeated at the Santa Fe Opera twice more, Aug. 13 and 21. Remaining tickets, if any, are available HERE.