Who wins—the director or the librettist?

By Peter Alexander June 18 at 11:18 a.m.

I was in New York recently. While there, I took the opportunity to meet a friend at the Metropolitan Opera, where we saw the new production of Salome by Richard Strauss.

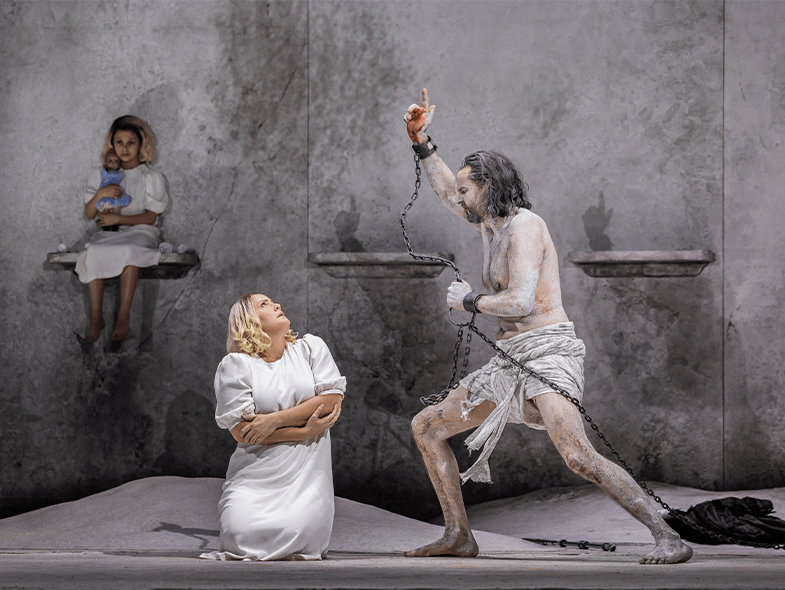

The production, starring Elza van den Heever in the title role and Peter Mattei as Jochanaan (John the Baptist) has attracted considerable attention, particularly for van den Heever’s performance. The singing I heard on May 24 ranged from solid to outstanding. Colorado native Michelle de Young, who has appeared at the Colorado Music Festival (2017 and ’18), was especially strong as Herodias. Conductor Derrick Inouye did not always manage to keep the orchestra under the singers, especially when they were singing from the back of the Met’s deep stage.

The production by director Claus Guth was in some ways a mess. Transferred to the Victorian era, it featured six young Salomes, all dressed like van den Heever in black velvet with a white collar, ranging in age from about 6 to early teens (the operatic character is supposed to be about 16). These young Salomes entered at various times during the opera, representing the abuse that Saolme has endured throughout her childhood, which explains her perverse sexual obsession with John the Baptist.

The child Salomes enter separately throughout the infamous “Dance of the Seven Veils,” each in turn having a simple black veil removed from her head before exiting. There is no seductive dance before Herod, which subverts the powerful music of the dance. In other mystifying additions, there are ram’s heads worn by members of the court, and a distracting scene of a near-nude woman surrounded by fondling courtiers played out on a raised area at the rear of the stage. The entire opera is placed in a sterile Victorian mansion.

All of which shows us that Herod’s court was degenerate and Salome is a damaged adolescent, which is pretty clear without directorial signposts. These ideas are often needlessly demonstrated in productions I have seen, from Santa Fe to Berlin. (Unsolicited advice for stage directors: Both the text and the music tell us that far better than your ideas will. Trust the music.)

But my purpose here is not writing a review of this production, which offers much scope for commentary. It is rather with a single question: to what extent should a production (and presumably therefore a stage director) honor the written text of the opera?

This is not an idle question, and in one sense Salome provides a good case study. The text of both Oscar Wilde’s English-language play and Strauss’s libretto, which is mostly a straightforward German translation of the play, are clear about one thing: in the confrontation between Salome and John the Baptist, he avoids looking directly at her. “I will not look on you,” he sings. “You are accursed!” And later, as she holds his decapitated head in her hands, she sings “If you had seen me, you would have loved me!”

For some directors, this is apparently just a line that is sung, and they feel free to play the relationship between Salome and John the Baptist as they want you to see it. If they want Salome to be a depraved teen seductress when she confronts John, they may have her writhing all over and around him; I have seen it done that way. Or if they want John to be tormented by her, they will have him grasping her, looking directly into her face, perhaps even twisting in agony with close physical contact; I have seen it played that way, too.

I would maintain that both of these stagings contradict the clear text that Strauss set. I believe that to respect the work, the director should honor the text’s clear indication that John turned away from Salome. Perhaps he saw her from the corner of his eye; perhaps she passed in front of him; perhaps he saw her figure when he first came into her presence. But he did not look directly into her face or deliberately interact with her.

That does not rule out interpretations in which he sees her but rejects her, or is in some way aware of her presence and her impact as a seductress. There are many ways to convey what is indicated in the text. But contradicting the text, in order to impose a single interpretation of the characters is unfaithful to the work.

Finally, “Depraved teen seductress” is certainly one way of understanding Salome, but there are others. Bored, spoiled adolescent living in a corrupt society; victim of abuse by a depraved stepfather; a tool in the hands of a scheming mother: any one or all of these are legitimate ways of understanding Salome.

For myself, I prefer a production that allows you to see many possibilities, rather than insisting on only one. But we live in a time of regie-theater, director’s theater, where unique and original interpretations are highly valued. But I still believe that original productions can and should stay faithful to the text of the work being presented.

What do you think?