Reviews of Tosca, Orfeo and Pelléas et Mélisande

By Peter Alexander Aug. 9 at 11:45 a.m.

Realistic, traditional productions are out. Most major opera houses today present re-interpretations of the original works, either transposed in time or symbolically represented to get at deeper truths within the artwork. At the Santa Fe Opera this summer, there were five productions, and each was presented in some kind of re-imagined setting. Every one offered some very strong musical performances, but the physical productions varied considerably.

Puccini’s Tosca (which I saw Aug.1) is the least re-interpreted of the summer’s five productions. It tells a story that is direct, brutal and melodramatic, a story of lust, piety, love, betrayal, and murder. Embedded in theatrical realism, it is not as suitable for symbolic or complex psychological representation as opera based in legend, myth, or literary symbolism. The current Santa Fe Opera production changes the time setting, but otherwise remains mostly faithful to the text.

The opera’s original setting—Rome in June 1800, during the Napoleonic Wars—is believably transferred to Fascist Rome of the 1930s, with few incongruities. That time period, shown by costumes, electric lights, an electric floor polisher and a camera, fits the main points of the story well. Scarpia is a believable representative of Mussolini’s regime. All the other characters—political prisoner, rebellious painter, operatic diva, pious sacristan and thuggish toadies—are types found in virtually any era.

However, not all updatings are equally successful. In the second act, designer Ashley Martin-Davis invented a cartoonish torture device with pulleys and levers that is more comical than frightening; Cavaradossi’s screams from an unseen room are more terrifying than watching him hoisted up and down with 1950s sci-fi electrodes attached to his head.

The substitution of electric lights for the iconic candles when Tosca stages Scarpia’s dead body was probably inevitable, but the effect is tame. I still don’t know how Tosca got blood on her hands from garotting the police chief, in place of the traditional stabbing, and Scarpia’s post-mortem convulsion was a shock without consequence.

Act III has some awkward moments. In spite of singer Joshua Guerrero’s best efforts, Cavaradossi’s collapse when shot is hampered by his being shackled to a post. The set does not allow Tosca to jump dramatically from the wall of the Castel Sant’Anglelo. Instead, she pulls out a gun she took from Scarpia and holds it to her head as she fades into darkness and another actor—a doppelgänger? A younger Tosca? A mysterious “other woman”?—rises from the floor and walks slowly into a gap at the back of the stage.

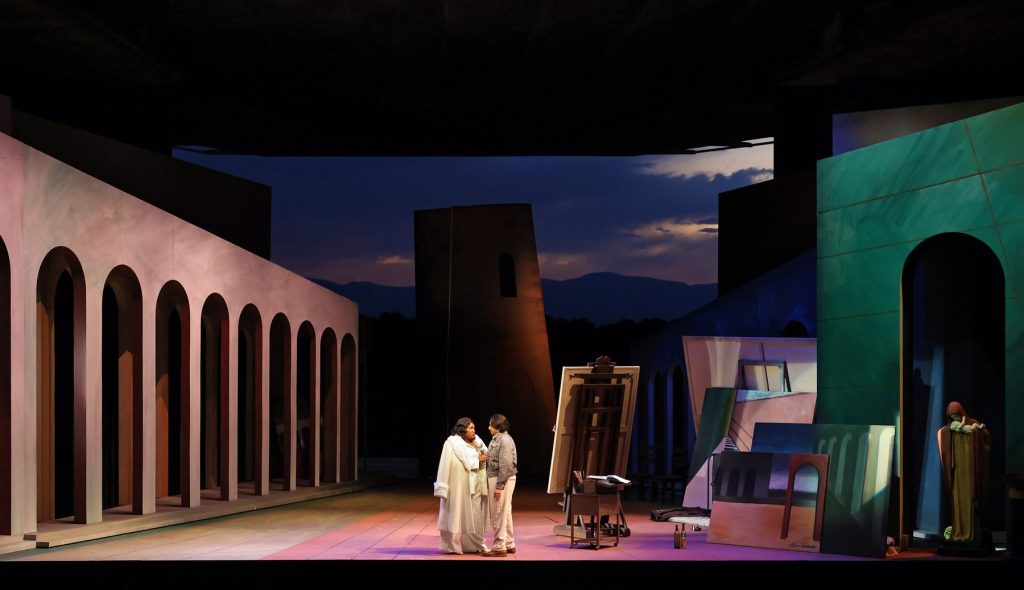

Martin-Davis’s minimal but serviceable set consists mostly of arcades of archways that can be moved around the stage during transitions, going smoothly from suggesting the church of Sant’Andrea della Valle in Act I, to Scarpia’s rooms in the Palazzo Farnese in Act II, to the Castel Sant’Angelo for the final act, with no attempt to duplicate the actual places.

The opening act features a tower at the back of the stage that provides an opportunity to portray Angelotti’s escape from prison via a daring rope descent by an athletic Blake Denson. This nicely fills in the background for his breathless appearance in the church and rush to hide in the side chapel before he is seen. We already know he is an escapee.

The Santa Fe cast is filled with strong voices. Joshua Guerrero brought a vivid tenor and a strong sense of style to his portrayal of Cavaradossi. His sense of control and shaping of phrases were strengths throughout, with only a slight moment of strain marring the final act. His aria “E lucevan le stelle” was carefully controlled, from a quiet, reflective opening to a bold ending.

Throughout he was a good partner for Leah Hawkins’ Tosca. Her soaring soprano met the part’s requirements well, with great intensity in Tosca’s fiercest moments. From her first entry in white furs that could have come directly from the glamour photos of the 1930s, she was every inch the diva, standing up to Scarpia’s threats and demands with appropriate hauteur.

As Scarpia, Reginald Smith Jr. conveyed well the brutal aspects of his character. But in spite of the gang of thugs that surround him, he is more than a back-alley bully. The aristocratic Baron Scarpia is polished as well as evil, and should display as much icy menace as overt threat. Smith sang strongly, never leaving any doubt of his power and brutality, but never quite conveyed the aloof and oily side of his character.

At the end of the first act, Smith showed Scarpia’s command of the crowd and the terror he inspires, through the strength of his voice and his powerful presence on stage. But this point went over the top when he was shown being worshipped by the crowd and choristers. That sight clashes with the singing of the Te Deum in an Italian cathedral; Scarpia knows how to observe religious expectations.

Denson sang well in the relatively small part of Angelotti. Dale Travis was fine as the pious and comical Sacristan, earning the usual laughs in the usual places. Scarpia’s unprincipled henchmen Spoletta and Sciarrone were well portrayed by Spencer Hamlin and Ben Brady. Kai Edgar was a strong and clear voiced Shepherd Boy. Dressed like Cavaradossi, he was heard not outside the castle walls but onstage alongside the prisoner.

Conductor John Fiore gave an idiomatic and stylish account of Puccini’s score, with all the flexibility necessary to keep the opera on track. The orchestra followed well, providing firm and lush support for the singers. Only once during the offstage cantata did the balance go awry; otherwise it was well controlled and the singers remained clearly audible and understandable throughout.

* * * * *

At the opposite end of the dramatic spectrum, Monteverdi’s Orfeo (Aug. 2) is based on the ancient myth of Orpheus’s descent to Hades and rescue of Eurydice through song, and is therefore at its heart symbolic in meaning. Alas, Santa Fe’s disjointed production is by turns stunning, baffling, effective and frustrating. It is the kind of production we see too often, filled with ideas, many ideas, without a unifying point of view.

As performed at Santa Fe, Monterverdi’s 1607 masterpiece has been orchestrated for modern orchestra by composer Nico Mulhy. This is not the first time Santa Fe has presented updated versions of Baroque operas. In the 1970s and ‘80s they presented three different operas by Francesco Cavalli as arranged and orchestrated by Raymond Leppard. That was a time when authentic Baroque orchestras and trained Baroque singers were in short supply, and Leppard’s arrangement brought works to life that we would not otherwise hear.

In the Santa Fe program book, Muhly justifies his arrangement using the same argument today. He writes, “The reason to orchestrate Orfeo for modern orchestra is so it can actually be done,” but that is no longer a valid position. It would certainly surprise musicians and audiences in Europe, where Baroque opera is frequently presented with original instruments and Baroque performance specialists.

Nonetheless, Monteverdi was the first great composer of operas, and Orfeo was the first opera to remain stageworthy, and any opportunity to hear this wonderful music is a cause for celebration. The cast, led by tenor Rolando Villazón in the taxing role of Orfeo, sang with conviction and commitment, if somewhat uneven application of Baroque performance style.

Villazón began his career with traditional tenor roles, including Rodolfo (La Boheme), Don Jose (Carmen) and Alfredo (La Traviata). He has more recently added Orfeo to his repertoire, with performances in Europe, and while he applies some appropriate ornaments, his overall approach is intensely expressive, with no holds barred for the top notes and the expressive highlights, of which there are many in Orfeo’s music.

Villazón showed signs of stress throughout the evening. And Monteverdi’s music speaks best for itself when presented with restraint and careful application of ornamentation to provide emotional emphasis. The use of modern instruments in the pit, with their capacity for greater volume than Baroque strings, cornetti and sackbuts, no doubt encourages the greater volume and more intense projection that Villazón applied, but they do not serve Monteverdi’s music well.

One exception would be Orfeo’s great Act III aria “Possente Spirto,” directed to Charon, the gatekeeper of Hades. Considered one of the greatest musical pieces of the early Baroque, this show-stopping number was sung by Villazón while suspended above the stage, apparently swimming in the River Styx as represented by rippling projections. Perhaps it was the harness that held Villazón in the air, or the aria’s length, but he sang with more restraint here than in most of the opera, and the less passionate approach allowed the aria to build carefully to its end. This was a highlight of the performance.

Another highlight was provided by Paula Murrihy as La Messaggera (The Messenger), who brings the news of Eurydice’s death. Her immobile figure against the darkening New Mexico sky behind the stage was striking enough, but she also sang beautifully, with a purity of sound that allowed the carefully applied ornaments to do their work and Monteverdi’s music to convey the depth of the tragedy with no unnecessary exaggeration.

Lauren Snouffer sang effectively as both La Musica and Speranza (Music and Hope), who first introduces the story and then conveys Orfeo to the gates of Hades. Her bright voice and straight tone allowed her to apply vibrato as an ornament, as is appropriate Baroque style. Eurydice has relatively little to sing, and Amber Morelai made the most of the expressive opportunities in her third-act aria.

James Creswell as Charon and Blake Denson as Pluto were appropriately sepulchral of voice. One is at a loss to accurately distinguish among the pastores and ninfe (shepherds an nymphs) who emerge from the chorus in brief solos, but they all fulfilled their roles well. The chorus sang with the rhythmic impulse that their dance-like music requires.

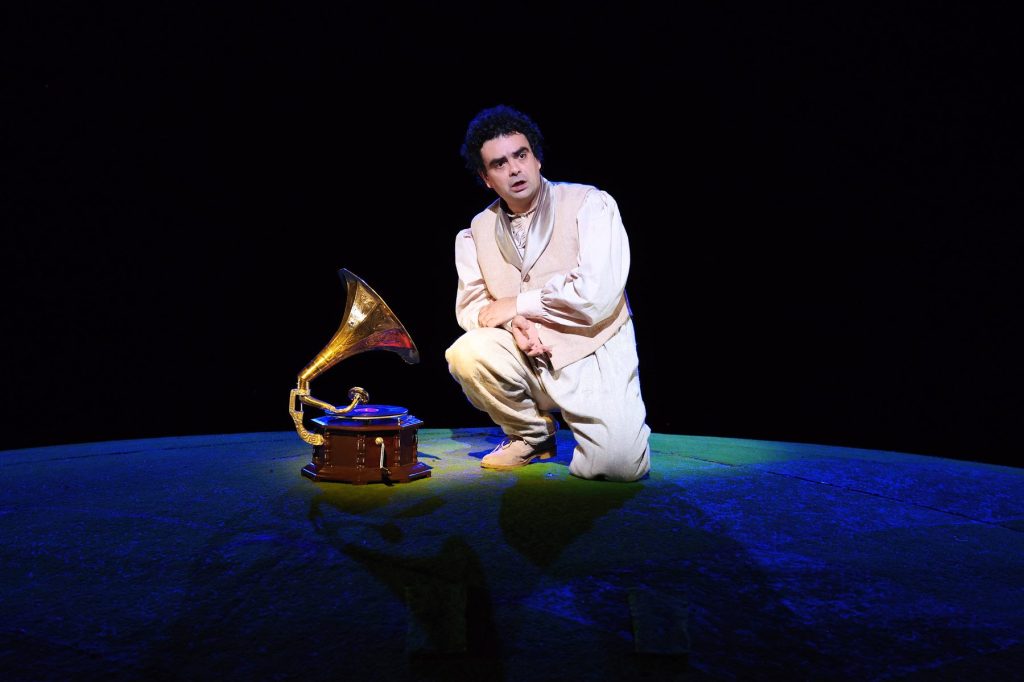

There are many confounding aspects of the physical production. Some of the effects—the stark imagine of La Messaggera against the sunset sky, well timed for early August, Orfeo’s swimming in the projected waves of light, and Speranza’s appearance on a rising moon in the last scene—are stunning. Others, however are not effective, or seem outright humorous. For example, Pluto presenting Orfeo with a golden gramophone—as a going-away gift?—induced chuckles. I have more ideas of what that might symbolize than one opera can encompass.

More problematic is the setting of the opening and closing scenes on earth (as opposed to Hades). The stage is filled with a large green mound that apparently stood for the idyllic fields where the shepherds and nymphs live and play, but it was awkward in the extreme. Singers had to balance carefully on its steepening slope, and slide down to stage level; it had to be clambered onto with effort; and it so filled the stage that there was no room for the chorus to dance, when their music is definitely dance music. The chorus costumes in orange and fuchsia conveyed anything but arcadian shepherds and nymphs.

I have other questions. Why were La Musica and later Eurydice in hospital beds? Why did the chorus dress up as birds, rabbits, and donkeys? These and other ideas show that stage director Yuval Sharon was busy thinking about all of the meanings embedded in the opera, as is his reputation, but not all the ideas contributed to the whole. Harry Bickett led the orchestra with sensitivity to the expression embedded in the Baroque style. Muhly’s orchestration reflects the original sounds as well as one could want with modern instruments.

But the question remains: is it really necessary to update Monteverdi’s operas for modern orchestra, when we now have so many accomplished orchestras and Baroque performance specialists in the world? Any re-orchestration is in effect a compromise with what Monteverdi wrote. Fifty years ago that was the only way we could hear professional-level performances of Monteverdi, Cavalli, Caccini, or in some cases even Handel. But we are past those days.

* * * * *

Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande (Aug. 3), based on a symbolist drama by Maurice Maertilinck, is imbued with multiple layers of meaning.

That was the intent of the composer, who said that his ideal librettist would be “one who only hints at what is to be said.” In the case of Pelléas et Mélisande, both the text and the music fulfill that ideal. Many elements of the plot hint at symbols, some clear and others not. Mélisande is found alone in the forest; Golaud exits the first scene saying “I’m lost too.”

Some symbols are clear: Mélisande’s hair that in most productions engulfs Pelléas, sheep that are lost and not heading home, the setting sun as Mélisande dies. Others seem meaningful, even when the meaning is murky: A ship sailing into a storm, Golaud taking Pelléas to smell the stench of death below the castle. Clear or not, the action conveys many meanings.

The production designed and directed by Netia Jones for Santa Fe Opera makes sure that you know that. Every major character has a doppelgänger who often moves in the background, or enters on the opposite side of the stage simultaneously with the actor singing the role. The fact that you may not know which is which until the singing starts certainly reinforces the murkiness, but it doesn’t help the audience.

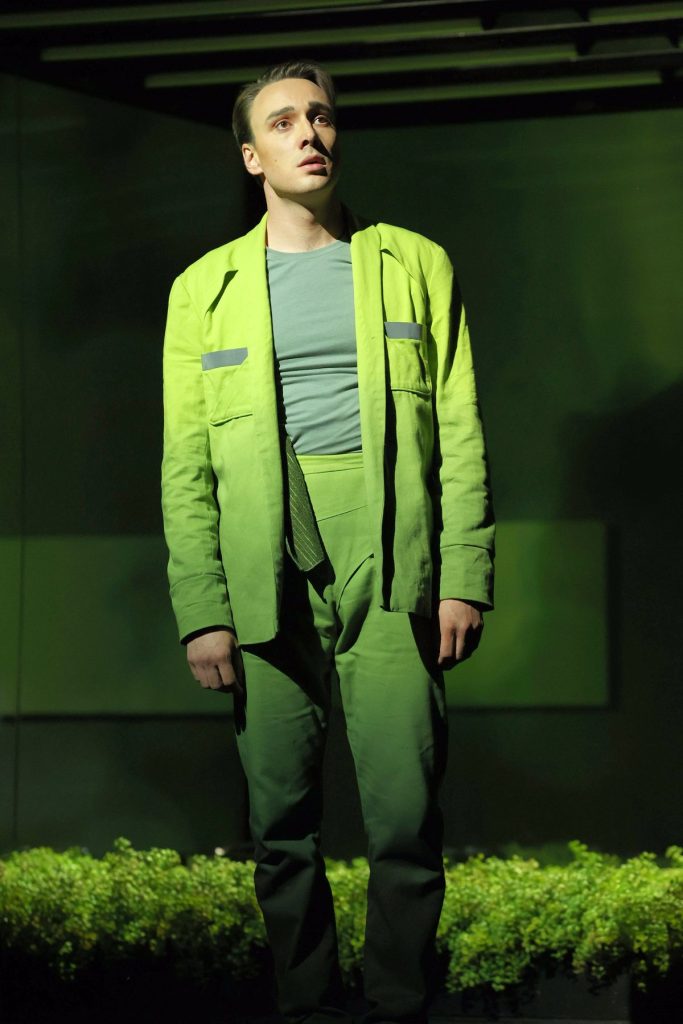

The costumes are essentially stylized modern dress—Pelléas wears white tennies and in one scene has a hoodie—but the time period is uncertain. The setting may be a post-apocalyptic time with the castle a sanctuary against the outside world that Mélisande fears. Projections suggest at different times an industrial setting, or a laboratory with chemical diagrams and texts projected on the walls. Outside scenes are suggested by projections of leaves or water.

And then there is the shadow box downstage left that rotates to offer a screen for shadows of the doppelgängers, or other projections that may or may not be the same as the walls. One open side provides a space for Goulaud’s bed after his riding accident, and Mélisande’s death bed in the final scene. Of the window she asks to be opened to the setting sun, there is no hint, which indicates that not all symbols of the original remain in Jones’s realization.

Another lost symbol in this production is Mélisande’s hair, which in the plot reaches from her tower to Pelléas below. At Santa Fe, however, her hair is not long enough to reach her waist, and when the time comes for her to let it down to Pelléas, she takes scissors and cuts off tufts that she drops.

Jones also added symbols, particularly with the character doubles. At the opening, Mélisande is sitting by a stream, with her double—drowned?—floating past, suggesting the character’s drift away from the real world. In one scene, the double of Pelléas and Mélisande moves slowly closer as the singers act out the text.

And there are curiosities in Jones’s direction. Arkel is nearly blind (shown by his darkened glasses) and only hobbles with a cane, yet he enters and exits down a steep spiral stairway before collapsing into a wheelchair. After his accident, Golaud is in bed, yet recovers fast enough to spring up to attack Mélisande. And why has Golaud’s sword become a knife—is that because of the modern setting? It is less menacing than a sword.

If piling obscurities on top of obscurities leaves the audience without a sure footing, the same cannot be said of the singers. Pelléas is as well cast as any production of this difficult work I have seen. Huw Montague Rendall’s Pelléas was clear voiced, secure into the top range, and eloquent. His voice sounded in turns clear, tentative, trembling, tender. It was a delight to hear such an expressive and well managed interpretation.

As Golaud, Gihoon Kim was solid, powerfully portraying the character’s growing menace. By the final scene Kim made his threat to the title characters palpable. Raymond Aceto was commanding as Arkel, the closest thing the opera has to a conscience. He used a rough hewn sound to convey his character’s age and infirmity, as well as an unsettled sense of moral authority.

Samantha Hankey sang Mélisande beautifully. Is it the director’s interpretation that she seemed more forthright and steady than the conventional, fragile Mélisande? Often immobile for long periods, she conveyed both hesitation and firmness, which added a different slant on her relationships. Susan Graham, well known and loved by Santa Fe audiences, provided just about the best French of the evening, and a memorable performance overall. She sang with the confidence of the veteran she is. As Geneviève, she commanded the stage in her short scenes.

Treble Kai Edgar made Yniold the vulnerable target of Golaud’s growing frustration. A sure-footed actor, he sang with a clear and precise sound; I only wish he had not been nearly covered by the orchestra so that his increasing fear could be heard more surely. As the physician, Ben Brady was a steady presence attending to first Arkel, then Golaud, then where he is usually seen, at Mélisande’s bedside.

Conductor Harry Bicket and the Santa Fe Opera orchestra capture the elusive quality of Debussy’s music, both the delicate sonorities and the constantly flexible rhythms. Pelléas et Mélisande is so steeped in French language and theatrical custom that it is difficult for most Americans to fully embrace. It communicates through the treatment of language more than melody. Even if one cannot grasp the subtleties, one can sense the subtle beauties even of a work that remains just beyond reach. Musically, Santa Fe provides that opportunity.

__________

NOTE: The remaining productions of the Santa Fe Opera’s 2023 season, Dvořák’s Rusalka and Wagner’s Flying Dutchman, will be reviewed in a later post.

CORRECTIONS: Minor typos corrected 8/9.