2023 Summer Season features three mainstage adaptations of the Bard

By Peter Alexander June 22 at 11:57 a.m.

Central City Opera (CCO) returns to a three-production mainstage season this summer for the first time in more than 10 years with three musical works based on Shakespeare.

The 2023 Festival season runs from Saturday, June 24, until Sunday, Aug. 6, with the three works performed in rotating repertory (see full list of dates below). The three works are musical adaptation of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet by French composer Charles Gounod, which stays close to the original plot in most respects (opens June 24); an opera by Rossini based on a French version of Othello that differs in significant ways from Shakespeare’s play (opens July 15); and Cole Porter’s Broadway hit Kiss Me, Kate, which uses Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew as a plot device in a broadly comic tale of feuding actors, interlocking love triangles and ruthless but luckless gangsters (opens July 1).

First to open is Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette, the closest of the three works to Shakespeare (performances June 24–Aug. 5). First performed in 1859, it was a huge success from the outset, with more than 300 performances over the next decade, and it remains popular today. This is largely due to the combination of a story that is familiar and much loved, and a beautifully written Romantic score.

“The music is fantastic!” director Dan Wallace Miller says. “Of all the adapted Shakespeare, its the one that fits the mold of French grand opera the best. It’s inherently French, and it has the sumptuous, flowing quality you expect.”

The opera has most of the major plot points of the play—the hatred between Montagues and Capulets, the Capulets’ ball where Romeo and Juliet fall instantly in love, the balcony scene, the deaths of Mercutio and Tybalt, and the deaths of the lovers in Juliet’s tomb. There are only a few differences from the original, Miller says.

For one, the play opens with a scene that is missing in the opera, a brawl between the Montagues and Capulets that sets the tone for the violence between the two families. “The other huge difference,” Miller says, “is that because this is an opera, you gotta have the final duo!” Instead of Juliet waking up to find Romeo’s corpse and then stabbing herself, as in the play, Juliet wakes up as Romeo is not quite dead yet. Only after their duet does he die, and then she kills herself.

Taking inspiration from Wieland Wagner’s minimalist stagings at Bayreuth after World War II, the opera is played in a bare unit set that represents the inside of a mausoleum. Different locations are suggested by changes in lighting, by moss, and by flowers, but the setting also symbolizes the pointless hatred that turns all of Verona into a mausoleum.

“The idea is that the ghosts will keep reliving this tragic story up until the point where humanity itself has forgotten that any of these people ever existed,” Miller says. “The people involved in the conflict don’t know what instigated it in the first place, but it has resulted in centuries of blood and tragedy.”

Miller also stresses that Romeo and Juliet are both children—she is specifically not yet 14, and he is probably a little older. “They are adolescents,” he says. “They are not the platonic ideal of romance. Romeo goes to the Capulet ball, and the first woman he sees he falls in love with. The realization that Juliet is the daughter of his enemy is a further turn-on—lust spurred on by rebellion.”

A challenge to the performers is the contradiction between very young characters and music that requires seasoned professionals. “It’s about adolescent love, but my God it’s so difficult to sing,” Miller says. “It’s absolute fireworks!

“Both Ricardo Garcia and Madison Leonard, who are singing Romeo and Juliet, are just doing a phenomenal job. It is so endearing to see that spark of adolescent glee in every interaction they have.”

# # # # #

Kiss Me, Kate (performances July 1–26) was Cole Porter’s greatest success. It opened on Broadway in 1948 and ran for more than 1000 performances, followed by a London West End production in 1951, and several subsequent revivals up to 2019.

The show is about actors trying to mount a musical version of The Taming of the Shrew, in which different cast members have different stakes in the show. Producer/director/star Fred Graham needs a success in order to revive a floundering career; co-star and ex-wife Lilli Vanessi is engaged to the influential General Harrison Howell, but also caught between her genuine love for Fred and his arrogant mistreatment of her. Bill, the boyfriend of younger actress Lois Lane, is involved with gangsters who attempt to hold the production hostage for his debts.

The entanglement of these different dilemmas creates lively theatrical humor. “The wit of (Kiss Me, Kate) is very sophisticated, acerbic, clever stuff,” stage director Ken Cazan says. “It’s amazing, the whole thing. But some of it’s dated. Something I have to deal with in 2023 is the misogyny that’s just through the roof.”

Cazan points to the original ending of the show, where Lois goes face down before Fred, as a sign of submission. He will talk to the cast and ask how they want to play that scene. “I think we’ll probably do a 180 from that,” he says. “I’m fascinated to talk to Emily (Brockway) and Johnathan (Hays), the two principals, and say, what happens after this?

“It’s up to them to perform it and I don’t want to force them into anything.” So if you want to know how this production turns out, you’ll have to see it!

In addition to the ending, the script is full of lines that are very troublesome in 2023—even the cheery tune sung by the gangsters, “Brush up your Shakespeare.” One line that is almost always changed today is when Lois sings to Bill, “Won’t you turn that new leaf over, So your baby can be your slave?” People from casual friends to CCO audience members to Pamela Pantos, managing director of Central City Opera, have told Cazan that they hate that line. It will be changed, he says, as it almost always is today.

The conception of the female roles is something else Cazan wants to modernize. He specifically mentioned Lauren Gemelli, the actor playing Lois/Bianca. “She’s so often done as a bubble headed sexpot, which is tremendously dated,” he says. “Lauren walked in (to her audition) and you could see the brains behind the manipulation. I’m very excited to work with her.”

The feuding between Fred and Lilli is supposedly based on real life. The show’s original producer, Arnold Saint-Subber, had seen on- and off-stage battles between legendary husband-and-wife actors Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne in a 1935 production of Taming of the Shrew. He later asked married writers Bella and Samuel Spewack to write a script based on Lunt and Fontanne, and they brought in Cole Porter to write the music.

It turned out to be a brilliant partnership. “Every song was a hit!” Cazan says. “I love it!”

# # # # #

The final show to open this summer will be Rossini’s Otello (performances July 15–Aug. 6). While based loosely on the same characters, this is not Shakespeare’s Othello that you may be familiar with. First performed in 1820, Rossini’s opera was based on a 1792 adaptation by French playwright Jean-François Ducis.

His Shakespearean adaptations in French included not only Othello, but Hamlet, Macbeth and Roméo et Juliette. Working in the late 18th century, Ducis was subject to the rigid rules of classical French theater, to the extent that some of his plays differed extensively from the original.

For his play, and subsequently Rossini’s opera, Ducis transferred the action entirely to Venice. In other differences, Otello and Desdemona are engaged but not married; Desdemona has another suitor, Rodrigo; Iago, another rejected suitor, pretends to support Rodrigo; and jealousy is less of a motivating factor than the racism that Othello encounters. As director Ashraf Sewailam explains, “Otello is referred to as ‘l’Africano’ multiple times by white characters, so the racist stuff is unambiguous.”

To shine a light on the racism, the production has been placed in classical times, where we can more easily notice its impact. “The central idea, staging it in ancient Rome, I credit to (CCO executive director) Pamela Pantos,” Sewailam explains. That setting avoids contemporary political sensitivities, while clearly highlighting racial animus within a diverse society.

The opera is not often performed today, for a variety of reasons. The greatest is simply that it has been overshadowed by Verdi’s Otello, which was first performed in 1887, 67 years after Rossini’s opera. Another reason is that it calls for four virtuoso tenors who can sing in Rossini’s highly decorated style. There are tenors today who can sing those roles, but as Sewailam comments, “they have to get them all four at the same time, obviously.”

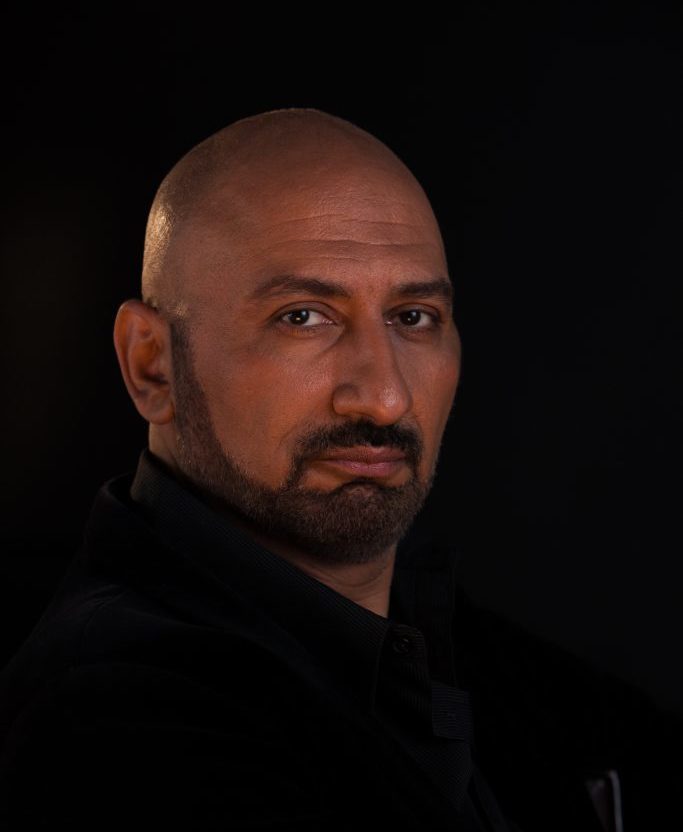

Sewailam has sung several roles at Central city Opera, but this will be his first appearance as director. He has directed smaller productions and scenes before—at San Diego Opera and dell’Arte Opera Ensemble in New York, among others—but he says directing a mainstage production in Central City is “a breakthrough for my directing.”

He sees the unfamiliar variant of the plot as an opportunity rather than an obstacle. “It’s a chance to highlight a different version of the plot,” he says. Instead, “the challenge is how the opera is structured musically.” Using singer’s slang, he says “the opera is really a ‘park and bark’ structure”—meaning a series of static arias where singers show off their vocal prowess without advancing the plot. But Sewailam has found plenty in the text for the production to transcend “park and bark.”

Like his fellow directors, he is excited about the singers he will be working with. “The cast is amazing!” he says. “We have quite a few twists and turns. We have a Black Iago, which presents both a problem and an opportunity, to mine the psychology of Iago and see what we can do with it.

“We are not contriving something that’s not there, but we want to mine everything to make it as compelling as possible.”

# # # # #

Central City Opera

2023 Season

All performances in the Central City Opera House

Roméo et Juliette

By Charles Gounod, Jules Barbier and Michel Carré

John Baril, conductor, and Dan Wallace Miller, stage director

Performed in French with English supertitles

7 p.m. Saturday, June 24; Friday, June 30

2 p.m. Sunday, July 2; Saturday, July 8; Wednesday, July 12; Saturday, July 15; Friday, July 21; Friday July 28; Sunday, July 30; Wednesday, Aug. 2; Saturday, Aug. 5

Kiss Me, Kate

By Cole Porter, Samuel and Bella Spewack

Adam Turner, conductor, and Ken Cazan, stage director

Performed in English with English supertitles

7 p.m. Saturday, July 1; Friday, July 7; Saturday, July 29; Saturday, Aug. 5

2 p.m. Wednesday, July 5; Sunday, July 9; Friday, July 14; Sunday, July 16; Saturday, July 22; Wednesday, July 26

Otello

By Gioachino Rossini and Francesco Berio di Salsa

John Baril, conductor; Ashraf Sewailam, stage director

Performed in Italian with English supertitles

7 p.m. Saturday, July 15; Friday, Aug. 4

2 p.m. Wednesday, July 19; Sunday, July 23; Saturday, July 29; Sunday, Aug. 6

Individual performance and season TICKETS

NOTE: Minor typos, punctuation and style errors corrected 6/22.